THE latest therapy in the treatment of severe asthma has been described as a “game-changer” by one of Australian’s leading experts in the field.

Conjoint Professor Peter Gibson, co-Director of the Centre for Healthy Lungs at the University of Newcastle told MJA InSight, in an exclusive podcast, that targeted monoclonal antibody therapy was changing the lives of about half the people with severe asthma.

In an editorial published in the MJA, Professor Gibson wrote that severe asthma represents “only a small part of asthma, perhaps between 1% and 3%”.

“But its impact is great, causing a significant quality of life and economic burden to people with the disease and to our community,” he wrote.

“Over 60% of the asthma health care spend is on severe asthma, and per patient costs are more than for type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or stroke.”

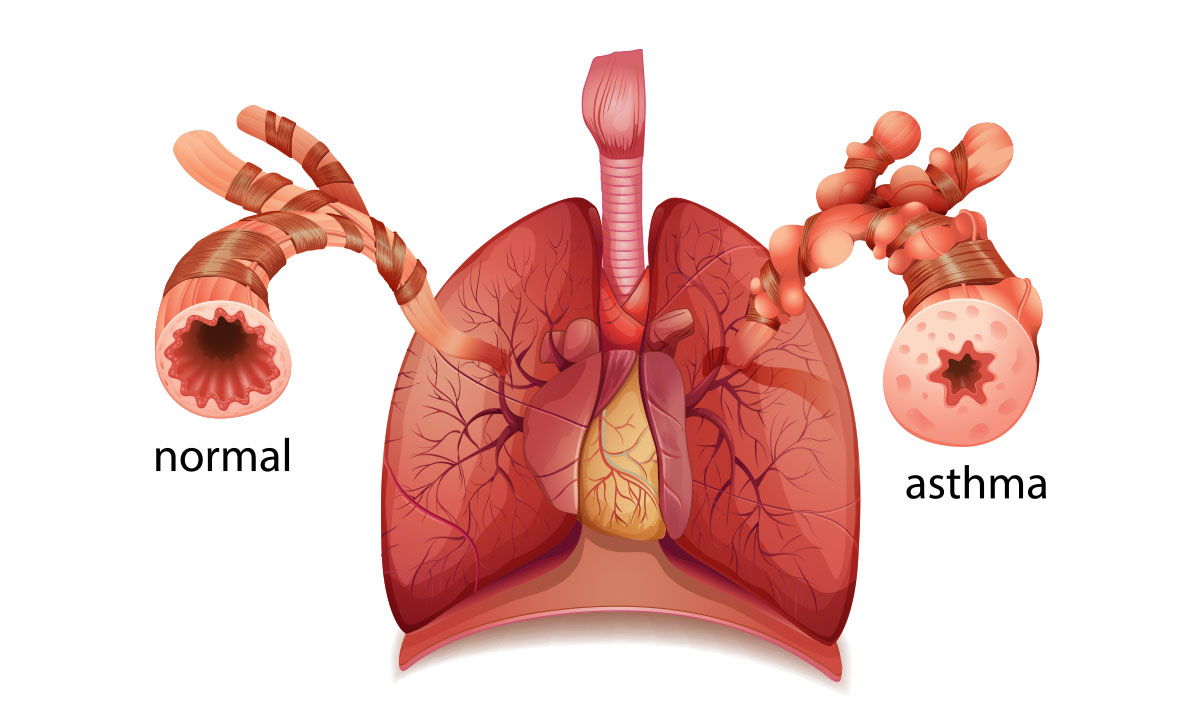

Severe asthma’s main feature is that it doesn’t respond to current therapies, Professor Gibson told MJA InSight.

“We have very good inhalers for mild and moderate asthma and when used properly and [if you’re] managing triggers, you can get good disease control in the majority of people,” he said.

“But they are poorly effective in people with severe disease. Because the puffers aren’t working, patients with severe asthma come to rely much more heavily on oral corticosteroids.

“Now, that’s good because it saves their lives, but it’s bad because of all the side effects: weight gain; easy bruising; thinning of the bones, [causing] osteoporosis, fractures; cataracts; it will exacerbate diabetes, which is a not uncommon comorbidity; patients report that they can’t get to sleep at night, and it affects their mood.

“[Taking oral corticosteroids is] not a nice thing if you can avoid it.”

And, the bad news is the corticosteroids are only partially effective for many patients with severe asthma.

“The good news is that some very bright people discovered this key pathway – it was an Australian, Colin Sanderson, who discovered the cytokine interleukin 5 (IL-5) – and that drives a very particular pathway in severe asthma called the eosinophil pathway,” Professor Gibson said.

Around 50% of people with severe asthma have the eosinophilic phenotype.

“And then, another group of scientists led by Paul Foster at the Australian National University proved that if you knock out the IL-5 gene you fix asthma, in model systems.

“People have gone on to develop specific monoclonal antibodies that block IL-5 and when given to people with severe eosinophilic asthma … you get a very dramatic response to treatment. It allows people who are on maintenance prednisone to reduce their dose at least by half and some people can come off it altogether.”

But what about the 50% of patients with severe asthma who don’t have the eosinophilic phenotype?

“There is good research going on in that area – predicting response and monitoring response,” Professor Gibson told MJA InSight.

“What’s opened up this area is the combination of the biomarker and a specific targeted treatment. If we can learn from that, not only discover new treatments but also find the biomarkers that go along with them that predict response, that’s going to make a huge difference to people.”

In his MJA editorial, Professor Gibson wrote that the assessment of severe asthma was complex and “requires cooperation and coordination between several disciplines”.

“This is because of the need to assess and optimise patients’ self-management skills, the need to manage the comorbid diseases that frequently occur with severe asthma and that may confound assessment of severe asthma, and the need for objective testing to establish the diagnosis and identify a specific patient phenotype.

“All of these boxes must be ticked in order to get the right treatment for the right patient.”

The targeted monoclonal therapy was a game-changer, but there were still barriers to access for some patients.

“We now have three monoclonals for severe asthma that are available on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme,” Professor Gibson told MJA InSight.

“That’s a great situation for patients with severe asthma. They are accessible, but it’s a fairly complicated process to access them and not all centres are geared up to put patients through that process.

“The actual implementation and model of care needed is still emerging.”

The model in the United Kingdom, in which the National Health Service commissioned designated centres that are accredited to deliver severe asthma services, might be “defeated” by Australia’s geography, he said.

“The UK model has a lot of appeal in terms of standardising care and concentrating expertise … [but] we need to respond by finding ways to deliver that service that’s appropriate for our population.

“We need to look at upskilling our clinicians, linking centres of expertise with regional centres and rural centres and we’re good at doing that in other areas. We need to simplify the assessment process.”

Professor Gibson referenced three online tools. Two are for clinicians – the Severe Asthma Toolkit from the Centre for Excellence in Severe Asthma and a tool from the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand. For patients, Asthma Australia has developed a resource.

Severe asthma is the focus of an MJA Supplement available at www.mja.com.au from Tuesday 17 July 2018. All the content of the Supplement is open access.

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert