WHEN a patient is given a diagnosis of sarcoidosis, their first port of call after their physician can often be Dr Google, an action that can lead to unwarranted anxiety.

Don’t panic, is the main message from Professor Paul Thomas, a consultant respiratory physician at the Prince of Wales Hospital and the UNSW Clinical School.

“When they hear they have sarcoidosis, they reach for the keyboard, which of course comes up with the most severe and usually fatal cases,” Professor Thomas told MJA InSight.

“Most are alarmed when they read about it, and they don’t need to be. What [Dr Google] doesn’t explain is that the vast majority [of sarcoidosis cases] don’t fall into those categories. They have a very good prognosis — 70% need no treatment and it will go away on its own.

“It’s only the smaller proportion of patients who actually have a form of the disease that needs long term immunosuppression or other major treatment. The majority do extremely well.

“Don’t listen to Dr Google.”

Professor Thomas is the senior author of a Narrative Review on sarcoidosis, which is published online by the MJA.

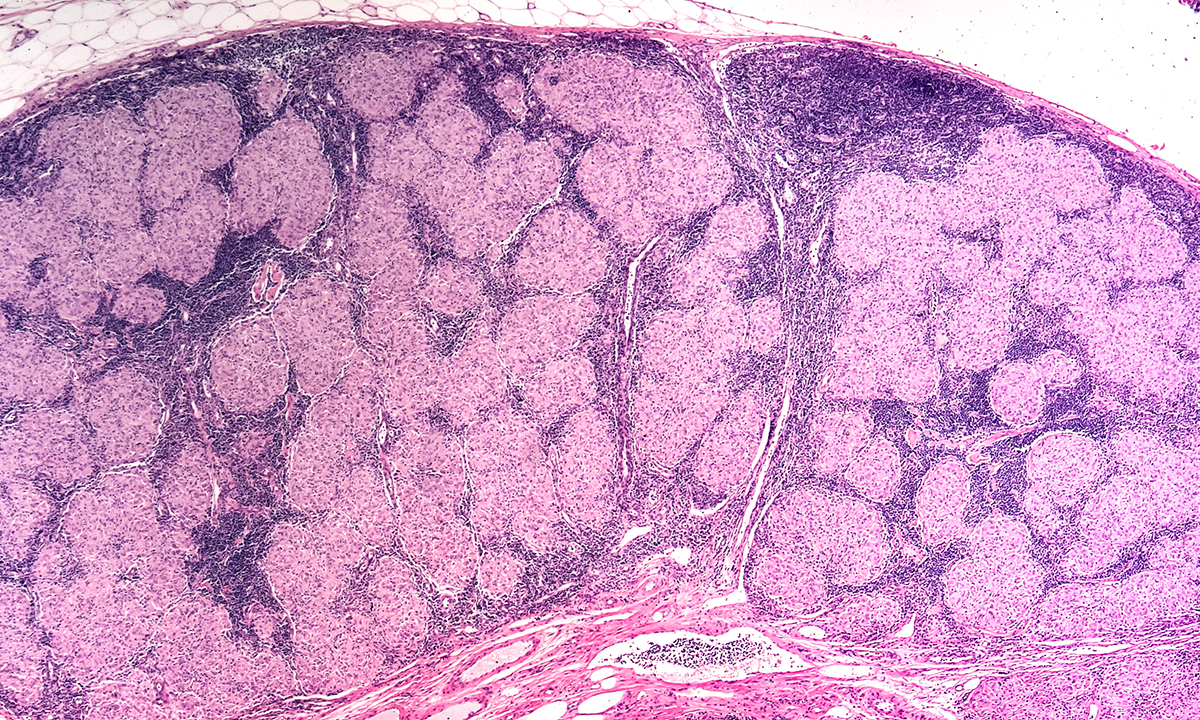

Sarcoidosis, the authors explain, is a “systemic granulomatous disease of unknown aetiology, primarily affecting the lungs and lymphatic systems, although any organ may be involved”.

“The presentation may be an incidental finding on chest radiology, or due to symptoms, most commonly cough or breathlessness, or relating to involvement of other organ systems such as the eyes, skin, nervous system or heart,” the authors wrote.

It remains, they said, a diagnosis of exclusion.

“It is very difficult to diagnose,” Professor Thomas said in an exclusive podcast.

“A lot of people say they’ve felt unwell for a number of years. Quite a few of them have probably had the disease for months or even years, and to make a diagnosis is very difficult because it’s subtle and varied in its presentations.

“The most acute form develops as an arthritis and red spots on legs or forearms. These last a few weeks, and if you do a chest x-ray at that time and you see lymph nodes in the middle of the chest, that’s a classic sign of an acute presentation of sarcoidosis,” he said.

“The worry with lymph nodes in the chest, of course, is that they are seen in other diseases, such as tuberculosis and lymphoma.”

A blood test – the serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) – is “an indicator of the total granuloma burden but has modest sensitivity and specificity, and is elevated in other granulomatous conditions, making it of limited utility in diagnosis and monitoring,” the authors of the Narrative Review wrote.

“If you’ve got a patient who is tired, or has a persistent dry cough, then doing a chest x-ray and an ACE level [test] can be helpful,” Professor Thomas said.

“They’re non-specific, but if they come back abnormal, then it does warrant doing a biopsy to [exclude tuberculosis or lymphoma] and confirm the [sarcoidosis] diagnosis.”

First-line management remains observation, he said.

“In the majority of patients, [sarcoidosis] doesn’t interfere with their lives. Some get complications such as fibrosis in the lungs that can gradually increase and they’re the ones we want to identify and try to prevent from getting worse.

“The majority we just observe for at least 5 years. If there is progression, we try and use corticosteroids for at least a year to reduce the inflammation caused by the disease. If it continues to progress, then we would add in an immunosuppressant, such as azathioprine or methotrexate.”

There is still much to be learned about sarcoidosis, Professor Thomas says, not the least of which is the aetiology and immunopathogenesis of the disease.

“Is it a single environmental agent [causing the disease]? It would fit; the lung is the most commonly affected, so it makes sense that an antigen or mycobacteria or perhaps propionibacteria might play a role,” he said.

“We do need better epidemiological studies to try and identify potential antigens. We don’t know what we should be avoiding.

“There are data that [show that] people who are associated with water contamination and mould may have a higher incidence [of sarcoidosis]. For example, there was a larger than expected number of firemen who were at the World Trade Center [after 9/11] who developed sarcoidosis. It was thought to be something either in the building or in the fire retardants they used.

“There’s a lot more to know.”

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert