ACUTE abdomen, if not assessed and treated expeditiously, can lead to mortality rates higher than those for heart attack and stroke, and yet Australian emergency departments (EDs) do not have a fast-track pathway for severe abdominal pain.

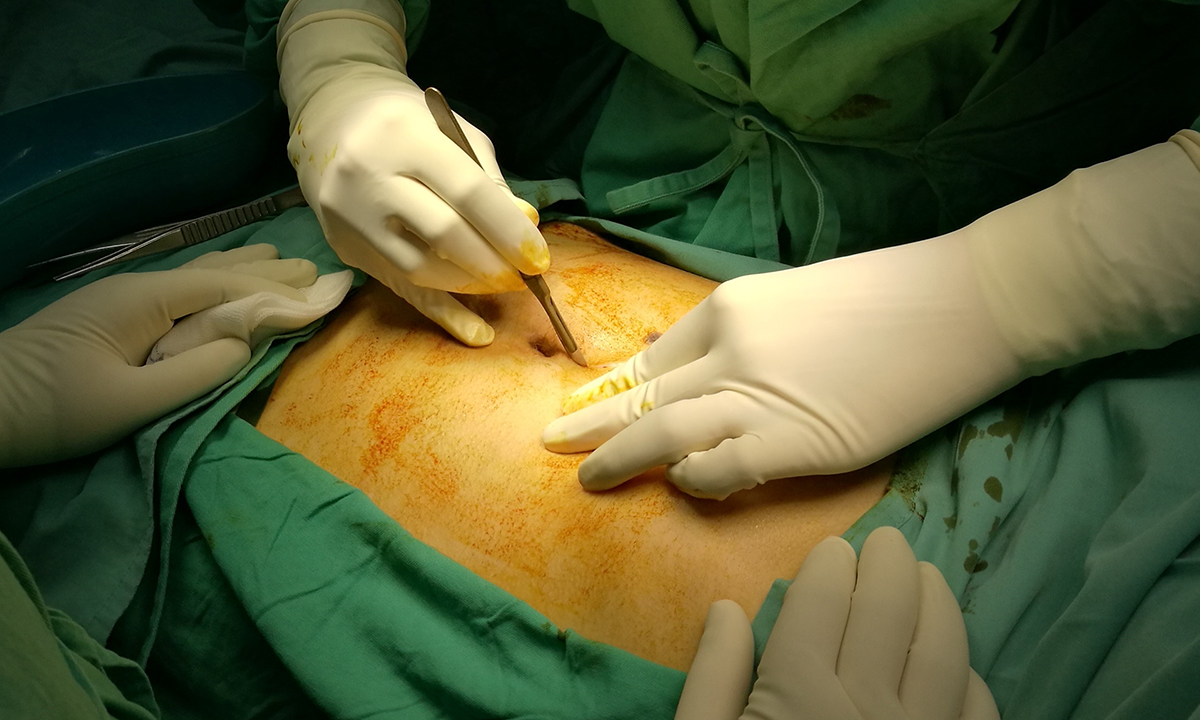

While evidence-based standards do exist for the management of a patient with acute abdomen and potential sepsis – a sepsis screen on arrival at the ED, blood cultures, antibiotics, lactate testing, computed tomography scans, a risk assessment to escalate care as appropriate, and post-operative admission to a critical care unit – it is the initial assessment on presentation that lacks the appropriate alarm bells.

According to the authors of a Perspective published today by the MJA, the overall predictive mortality of acute abdomen is 8–15%, and double that for patients aged 80 years and over.

“The consequences [of delayed assessment and treatment of acute abdomen] are actually worse [than for heart attack and stroke],” Dr Katherine Broughton, a co-author on the MJA article, told MJA InSight in an exclusive podcast.

“The mortality rate for a patient having an emergency laparotomy is much higher than the chance that a patient dies following a heart attack or stroke.

“The potential diagnoses are multiple, there is no single blood test. It’s a higher risk group and we should be putting more attention into managing these patients, and that is why we need these pathways.”

In the UK, findings of a 14.9% 30-day mortality rate for emergency laparotomies prompted the National Health Service to set up the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA) across England and Wales, with data collection commencing in 2012 and the third report published in 2017.

“Improved care, as demonstrated by a reduction in average length of stay of almost 3 days, represented a cost saving of £30 million per annum in bed days alone,” the authors of the MJA Perspective wrote.

Dr Broughton said that Australia had much to learn from NELA.

“We’ve been a bit slow on the uptake of some of the work done in the UK in regards to … improving the care of patients with emergency laparotomies – 5–7 years behind,” she said.

“It’s a difficult group of patients to look at … but it is very clear that there are standards of care that we should be meeting. It’s often the simple things – early antibiotic treatment, getting them early to the operating theatre in the appropriate timeframe, making sure the right people are operating on them.”

Dr Broughton was a colorectal fellow at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital in Perth, and now works at Western General Hospital in Edinburgh. Late in 2016, along with co-author Dr Robert J Aitken, a Perth colorectal surgeon, and a group of surgical colleagues at Sir Charles Gairdner, she undertook a 12-week prospective multihospital audit using inclusion and exclusion criteria similar to those of the Emergency Laparotomy Network. The audit included compliance with a care bundle and a documented prospective risk assessment, similar to NELA’s.

“The audit recorded a low 30-day mortality rate (6.6%); however, as almost three-quarters of the emergency laparotomies were performed in a principal referral hospital, the results may not be typical of Australia,” Broughton and Aitken wrote.

Dr Broughton told MJA InSight that despite the low mortality rate, WA “failed to meet standards of care across the board”.

“That dichotomy is a little difficult to understand,” she said.

“It may be a cultural difference in selecting patients who are actually going to survive an operation. I think Australia is better at acknowledging the patient who’s not going to benefit from surgery and is going to die regardless.

“We’re better at talking to patients and their families frankly about it, and actually selecting the right patients [for surgery].”

As a result of the WA audit, the Royal Australian College of Surgeons and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists are setting up a binational audit and quality improvement project which will – hopefully – get started in the middle of 2018.

“We saw that we very clearly needed some national data, and … we needed prospectively collected, high quality data and, at the same time, we need to look at quality improvement,” Dr Broughton said.

Apart from improved outcomes for patients, the WA audit also highlighted the financial benefits of developing a fast-track pathway for acute abdomen.

“Most of the cost estimations are based on reducing length of stay in hospital,” Dr Broughton said.

“A night in hospital is expensive. What really makes a difference is getting patients home earlier, appropriately so. NELA reduced length of stay by 2 days between the first and third years.”

The bottom line for Australia?

“If we reduce length of stay by one day, then based on the cost of one night in hospital, we could save $34 million in a year.”

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert

“I do not think anyone is proposing that all patients get a CT, or all patients with belly ache get put on a standardised pathway. Nor are they suggesting that all patients with abdominal pain get antibiotics.” says Anonymous Person, but then “The authors paper shows risk assessing patients affected outcome- so clinical judgement alone is inadequate to judge clinical acuity.”

If we can’t use clinical assessment, but we’re not putting everyone on a pathway, what does Anonymous Person suggest we do?

I do not think anyone is proposing that all patients get a CT, or all patients with belly ache get put on a standardised pathway. Nor are they suggesting that all patients with abdominal pain get antibiotics. And agreed, there may be a portion of negative laparotomies although these are become more uncommon these days. I think the focus is on identifying the sick patient and those patients getting appropriate investigation and management. The authors paper shows risk assessing patients affected outcome- so clinical judgement alone is inadequate to judge clinical acuity.

The author’s paper also suggests that even septic patients (using two types of septic scoring systems) did not receive timely antibiotics. I suppose while we think that the overtly septic patient with abdominal pain would get urgent antibiotics, it does not appear that they actually do. And those with clearly a need of an operation and a risk of dying of over 10% do not reach theatre in the timeframe recommended by evidence.

The problem with the acute presentation ofpatients with “acute abdomen” or “sepsis” is that they don’t come with those labels imprinted. Particularly in the elderly, symptoms and signs are often vague. The strategies that fast-track patients with potential “sepsis”, if applied without clinical thinking, channel too many people to early antibiotics, which, when inapprorpiately prescribed, create their own harms.

We need to find a balance between the use of clinical skill and “pathways” – without that skill, the wrong patients end up on the wrong pathways, and alternative harms occur.

Ray Hyslop is right – the negative laparotomy rate can never be zero, and over-use of investigations creates injury through over-diagnosis, excessive radiation, cost and anxiety.

The issue is not just within EDs. The issue is streamlining the process to ensure the sick patients get the expedited care they need. Triaging patients helps but it’s appears there are other failures such as antibiotic therapy which should be given early in the septic patient – and that would be in ED. The paper the authors wrote showed poor adherence to early antibiotics within the septic patient.

When I graduated 60 years ago there was one way of investigating an ” acute abdomen”, laparotomy. It appears that no laparotomy or laparoscopy can now be performed until various investigations have been done. Sue Ieraci is right on the money. Only people with experience should staff A&E Departments and waiting times would be slashed if nobody less than a PGY2 was allowed to work there.

The title opening paragraph of this article by Swannell is mischievous if not libelous, and suggests that lives are being lost and millions of dollars wasted because of failings in “Australian Emergency Departments”. As the article and UK evidence makes clear, the keys include access to theatre, standardised anaesthetic, post operative care etc. Australian results are already superior to those elsewhere. Yet apparently, once again, the problem is the “Australian Emergency Departments”. Disgraceful medical journalism.

Abdominal pain is a common presentation to ED for elderly patients. Only a minority have acute abdomen with sepsis – generally indicated by physiological derangement and acute severe pain. It is these features in history and physiological observations that are used to prioritise patients at ED triage. If the authors are proposing that all patients presenting with abdominal pain enter a pathway of investigation, more over-testing and over-diagnosis will follow. Triage should be according to presenting symptoms and physiological observations – not potential diagnosis. Otherwise, the triage scale is so highjacked as to become meaningless.

I suggest that the best way to minimise delay for these patients is to have enough staff of sufficient skill in EDs to identify them, and then a seamless response to surgical referral – prioritising clinical patient review over the ordering of more tests.