AUSTRALIA will have to boost its provision of low vision rehabilitation services to cope with rising rates of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), say the authors of a new study of the prevalence of the disease.

The research, published in JAMA Ophthalmology, found that around 1% of Australians over the age of 50 years, and nearly 7% of those aged over 80 years, had late-stage AMD, a condition that leads to blurred or no vision in the centre of the visual field. Rates of early and intermediate AMD, which can be asymptomatic, were much higher at 15% and 10%, respectively.

Rates of AMD were considerably lower in the Indigenous population, for whom the disease is relatively rare. The study authors say that it is not clear why this should be so, but that people with higher levels of retinal pigmentation may be protected from oxidative damage. Lower life expectancy in Indigenous populations may also play a role, given that increasing age is a key risk factor for AMD.

Co-author Dr Stuart Keel, a research fellow at Melbourne’s Centre for Eye Research Australia, said that AMD remains a leading cause of loss of vision, accounting for around 70% of all blindness cases in Australia.

“It is a major issue, and with increasing life expectancy, what this means is that we may need to improve access to and increase the number of low vision rehabilitation services to cope with this growing burden in the future,” he told MJA InSight.

The key risk factors for AMD are increasing age and a family history of the disease, although smoking is known to have an effect and there is also evidence that a diet rich in fish and leafy greens may be protective.

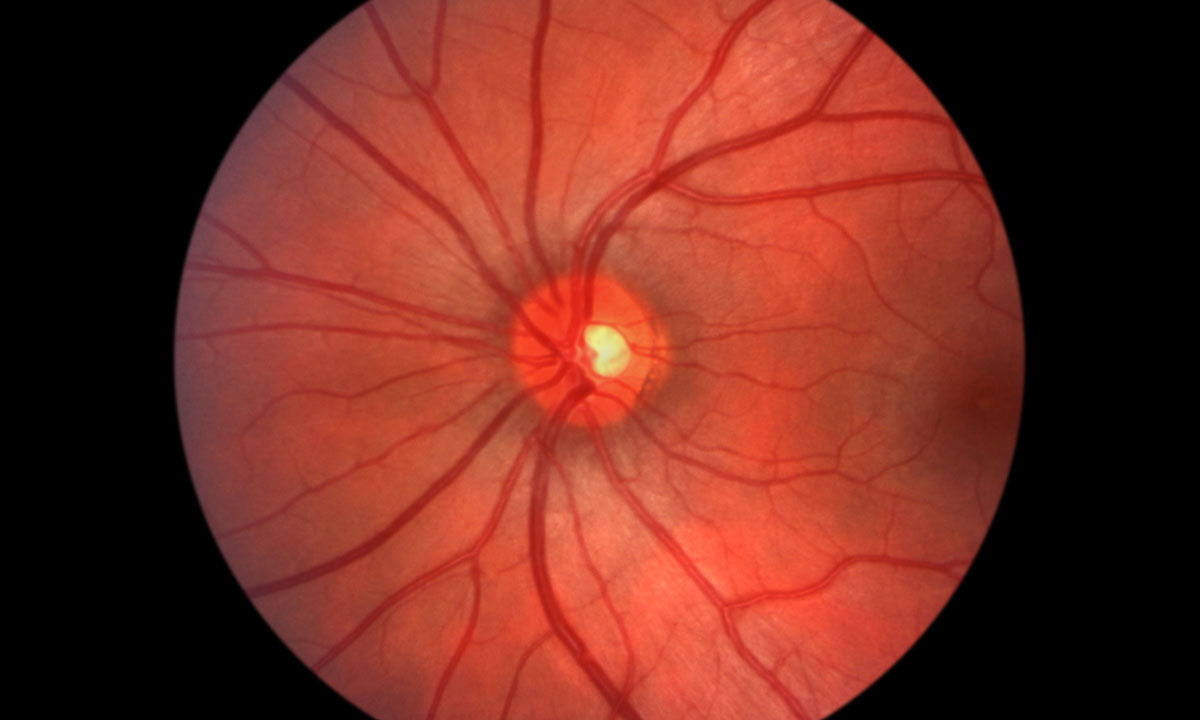

There are two types of late AMD, known as atrophic (“dry”) and neovascular (“wet”). The study found that about 75% of cases of late AMD are of the dry variety and 25% are wet. Unfortunately, there are no treatments for dry AMD currently, although there is an effective therapy for the wet version.

“Wet AMD is a result of abnormal growth of blood vessels in the eye. These have weak walls, which leak fluid into the macula,” explains Stacy Vueti, an orthoptist practising on the NSW north coast. “Treatment is regular injections of antivascular endothelial growth factor into the eye, which will seal some of the blood vessels and give the eye a chance to dry out.”

The injections, which have to be repeated every 1 to 2 months, stabilise and sometimes even improve the AMD.

“But what people need to understand is that the earlier the diagnosis, the earlier the treatment starts, and the more chance there is of a good outcome. Leave it too long, and the macula can get permanently scarred,” Ms Vueti said.

She said that people with AMD in only one eye who were most likely to get diagnosed late.

“If you develop the disease in one eye and it’s not your dominant eye, you may not pick up on the loss of vision for quite some time.”

But even with the non-treatable dry AMD, it’s important that people get diagnosed as early as possible, Ms Vueti added.

“Even if the condition can’t be treated, people will need help if they want to continue leading an independent life. Organisations such as Vision Australia can help people do that. There are strategies and equipment to allow people to continue cooking, making themselves a cup of tea, read their own mail, manage their finances – a variety of things that they may feel they can’t do any more. Providing these kinds of services is also a boon for the government, because if we can help people stay in their own homes, it saves money.”

Dr Keel said that one finding of the study was that a large proportion of the at-risk population were not having regular eye checks, increasing the risk of undiagnosed eye disease.

“We need to reinforce and increase public education on the importance of having regular eye examinations, particularly if you are in an at-risk group, which is anyone over the age of 60 years, and particularly if you have a family history of AMD.”

He said that in its early stages, not only was AMD asymptomatic, but so were other common eye diseases, such as glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy.

Dr Keel said that GPs have a role to play in educating patients and making sure that older people were having their yearly or 2-yearly eye examinations.

“If patients do present with central reduction in vision, quite often that might be cataract disease rather than AMD. But in any case, it’s very important to refer these people directly to an optometrist or ophthalmologist.”

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert