IN 1810, English novelist Fanny Burney felt a pain and hardness in her right breast. Her doctor diagnosed breast cancer and advised surgery, performed without anaesthetic in that era. On the day of her surgery, seven “men in black” entered her room and compelled her to remove her gown. She refused to be held down, but when “the dreadful steel was plunged into the breast, I needed no injunction not to restrain my cries”. Burney could feel the knife “racking against the breast bone – scraping it” as the mastectomy proceeded.

Thankfully, much progress has been made since these gruesome beginnings of breast cancer treatment. One enduring advance came at the other end of the 19th century, when the effect of radiation on cancer was first investigated. In 1896, a year after the discovery of x-rays, Emil Grubbé became the first physician to use radiation in the treatment of breast cancer.

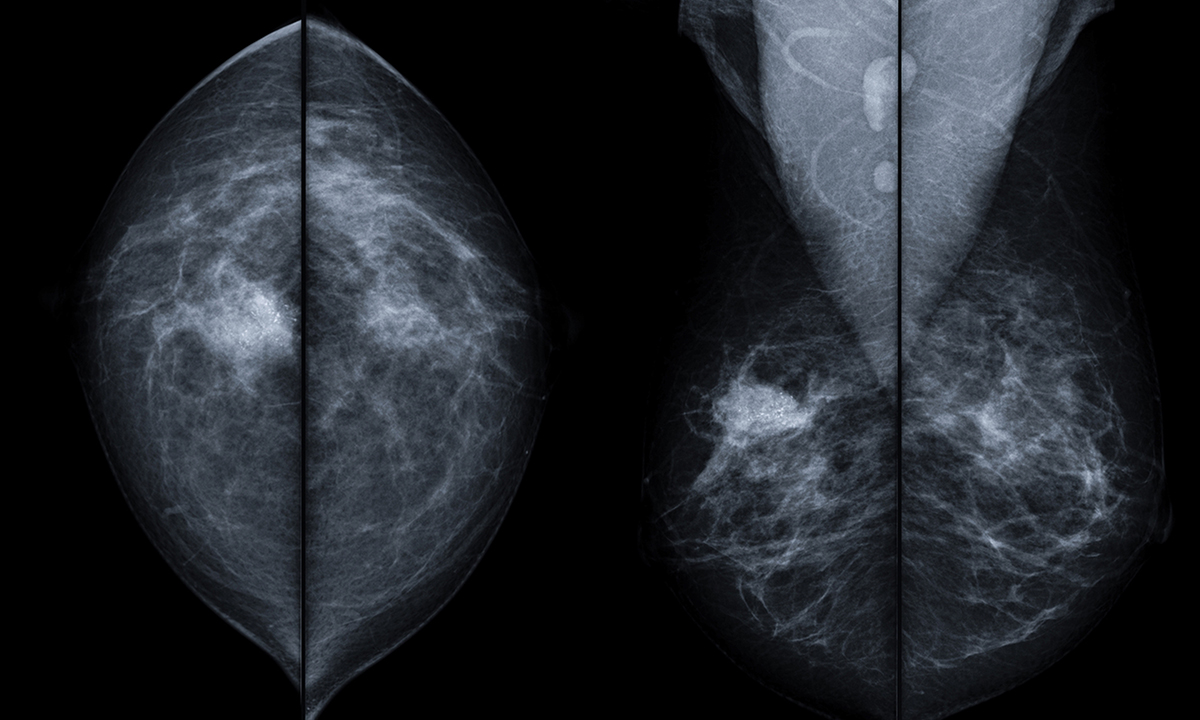

Radiation therapy (RT), now a mainstay of treatment for early breast cancer, has evolved considerably over the past 20 years. In a new Narrative Review published in the MJA, Professor John Boyages, a radiation oncologist at Macquarie University, surveys the findings of the most recent trials and research into radiotherapy for early breast cancer.

The latest evidence shows that radiotherapy reduces local recurrence and breast cancer mortality rates after lumpectomy for all patients, as well as for node-positive patients after a mastectomy. Researchers have yet to identify a subset of patients after breast conservation surgery who can safely avoid RT.

Other key findings in the review are:

- short courses of RT over 3–4 weeks are generally as effective as longer courses;

- a radiation boost reduces risk of recurrence in the breast, but can be omitted in older patients with clear margins and a good prognosis;

- axillary recurrences can take a long time to appear, with more than a third occurring after 5 years;

- leaving disease untreated in regional nodes may reduce survival; and

- not all patients need RT after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and mastectomy.

Dr Verity Ahern, a radiation oncologist at Westmead Hospital and Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Sydney, says that there have been three main developments in radiation therapy for early breast cancer over the past couple of decades. The first of those is the introduction of multidisciplinary care.

“Women’s cases are presented to multidisciplinary teams at a regular meeting, so there’s a very good dialogue between surgeons, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, pathologists and radiologists, and that is vital to making decisions about each of the treatment modalities for the individual patient,” Dr Ahern told MJA InSight.

Another key driver of better care is the development of new technologies for radiation therapy.

“Enormous improvements have been made in understanding the radiation dose distribution better, and being able to define the dose distribution more precisely. This has led to fewer acute and long term side effects, so that’s a big change. But it requires huge skills from the radiation therapy team and it’s very computer-driven.”

Dr Ahern said that the third significant development was a better understanding of tumour biology.

“We can use this [understanding of tumour biology] to inform decisions about which areas we should be treating – is it partial breast, whole breast, or the chest wall? Is it lymph node areas as well as breast or chest wall? These are the kinds of questions we’re getting better at answering.”

Dr Ahern said that the current Australian standard of care for all women with early breast cancer is radiotherapy after breast conservation surgery, although there was some controversy as to whether there were any women who could forego RT.

“There is a study that is about to open which is investigating in the Australian setting the omission of radiation therapy in women at low risk of recurrence of breast cancer based on biological features. So, this [study] might give us some answers. But for the moment the recommendation is not to avoid RT in any woman with early disease.”

She said that there had been a definitive move in recent years towards shorter courses of RT, and that Cancer Australia guidelines had recently been updated to reflect that.

“Nowadays, the question would be why aren’t you giving shorter courses in women with early breast cancer. There’s not a magic number of patients we should be aiming towards, but you need to find a reason to give longer courses of RT in women with early breast cancer.”

On intra-operative RT, a relatively new technique where radiation is given during surgery directly to the cavity where the cancer used to be, Dr Ahern remains cautious.

“There are pockets of surgeons who think it’s a good idea. But a lot of radiation oncologists are very concerned that we might start to see a higher rate of local recurrence with the technique,” she explained.

“Intra-operative RT is basically irradiating the rim of the surgical cavity, whereas conventional RT is irradiating the whole breast. The reason for treating the whole breast is that you do see recurrences away from the cavity. Intra-operative RT may be missing microscopic cancer cells that can be quite some distance away.”

Dr Ahern said that technological evolution will continue to improve radiotherapy, but there would be a limit to it.

“The real breakthroughs will come with understanding the biology of breast cancer at the genome and proteome level. That will inform us as to which particular patients are going to benefit from RT and which ones can safely avoid it. But it will also help us to understand which particular areas need to be targeted, which lymph gland groups, and whether to treat them or not.”

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert