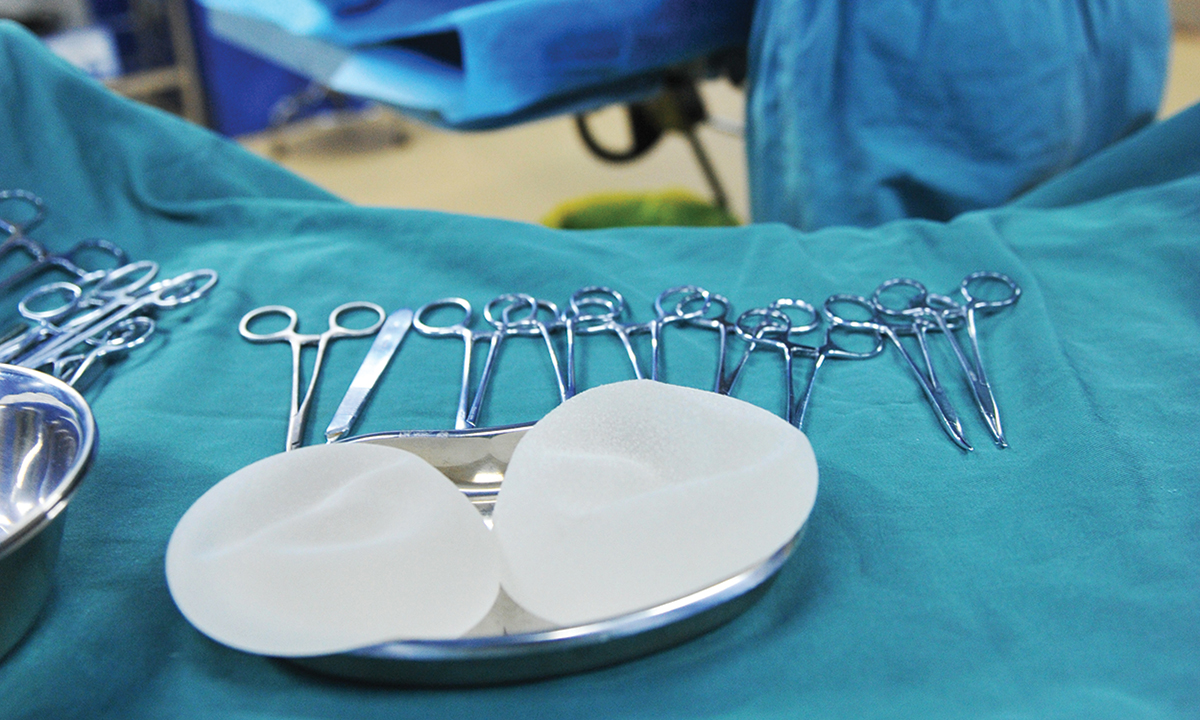

SURGEONS and breast device manufacturers are being urged to provide data to the Australian Breast Device Registry, in light of growing evidence of a causal link between some breast implants and a rare type of lymphoma.

Writing in the MJA, experts have called on the Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons, the Australasian College of Cosmetic Surgery and Breast Surgeons of Australia and New Zealand to require their members to provide data to the registry as a condition of membership.

The call comes after the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) was the first regulatory authority in the world to confirm the likelihood of a causal link between breast implants and breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) in December of 2016. The TGA confirmed that 53 cases of BIA-ALCL had occurred in Australia between 2007 and 2017, including three deaths in Australia and one in New Zealand. The cases occurred 3–14 years after implantation, with a median interval of 8 years.

The experts have also called for manufacturers to provide ongoing sales data to enable the registry to validate its case capture, and to financially support an appropriate registry for post-marketing surveillance.

Speaking to MJA InSight, co-author Professor Anand Deva said that the registry was an important tool to shed light on the whole breast implant industry.

While patients with implants for post-cancer breast reconstruction were well studied, Professor Deva said that relatively little was known about the long term outcomes for patients with implants for cosmetic purposes.

“It’s a big black hole,” said Professor Deva, who is Professor of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Macquarie University.

“That’s why the breast implant registry is such an important tool – it’s hoping to capture all women,” he said, noting that Macquarie University was also hoping to set up a walk-in implant surveillance clinic to provide better surveillance of women who travel overseas for breast implant surgery.

BIA-ALCL has been associated with textured implants with large surface area, which have become increasingly used in Australia in the belief that they reduce the risk of capsular contracture, Professor Deva said. The TGA estimated the risk of the condition to be low at between 1 in 1000 and 1 in 10 000 women with implants.

Dr Ingrid Hopper, head of Drug and Devices Registries at Monash University and lead author of the MJA article, said that the registry was key in providing real world data on long term patient outcomes.

“[BIA-ALCL] is a rare disease with a median time of onset of 8 years after implant insertion. Clinical trials of the [scope] and length necessary to identify this complication will never be run; therefore, the only way to pick this up is through post-marketing surveillance with ongoing systematic monitoring of patients after they receive their implant,” Dr Hopper said in an MJA InSight podcast.

The registry was rolled out nationally in 2015 and is seeking to capture 95% of Australia’s estimated 20 000 breast implant procedures annually. To date, 300 surgeons have contributed data from more than 17 000 patients.

The MJA authors said that the registry dataset may be able to help evaluate the strategies proposed to reduce the risks from breast implants.

“In the case of BIA-ALCL, this includes evaluating improvements in surgical techniques using a 14-point plan to reduce the risk of biofilm formation, and considering recommended lifespan in vivo of less than the median interval to develop BIA-ALCL for textured and polyurethane implants.”

Dr Daniel Fleming, spokesperson for Australasian College of Cosmetic Surgery, said that the college supported the registry 100%.

“The registry is extremely important, and we believe it should be compulsory for surgeons to contribute data. It will be a way to monitor the incidence of complications such as BIA-ALCL,” said Dr Fleming, who chairs the college’s BIA-ALCL safety committee and was a member of the TGA’s expert advisory committee on the condition.

However, Dr Fleming added that the registry was only as good as the quality of its data. “The registry is not yet compulsory, so is not capturing all cases and it does not capture complications that do not need surgery,” he said. “We need to be cautious about how we draw conclusions from the registry in the short to medium term.”

Additionally, he cautioned against the “over-enthusiastic” interpretation of its data because the registry “is not a prospective clinical trial”. For example, he cast doubt on the ability of a registry to evaluate the 14-point plan, which he said was essentially a guideline for surgeons.

Also, Dr Fleming said that it was not the role of a registry to suggest removing textured and polyurethane implants before the median interval of 7 years to develop BIA-ALCL.

Dr Fleming added that it was important to consider the rarity of BIA-ALCL in any recommendation to remove implants prophylactically.

“Let’s assume that the rate of BIA-ALCL for textured implants is 1 in 1000 – the highest estimate in the TGA recommendations – still 99.9% of women with [textured] implants will never get it,” he said.

Dr Fleming said that textured implants were the most commonly used implants in Australia, which was likely to result in a wave of BIA-ALCL in the coming years. However, he said, yet-to-be published research, of which he is lead author, shows that some cases of BIA-ALCL may be self-limiting.

Textured implants have been used in Australia since the early 1990s, Dr Fleming said, but confirmation of the first case of BIA-ALCL was not until 2007.

“That’s 16 years and we know 95% of the cases should have occurred by then. Where are they?” he said.

Dr Fleming said that there was no reason to suppose BIA-ALCL didn’t exist in patients with textured implants before we started testing seromas for it in 2008, and cancer data had not shown an increase in deaths from other invasive lymphomas in women with breast implants in this period, ruling out misdiagnosis.

“This leaves us with only one possibility – it went away or remained indolent,” he said, noting that the upcoming research would describe two cases in which the BIA-ALCL was shown to spontaneously 95% regress or resolve completely.

“Here’s the problem, though. With the seroma presentation, we don’t yet have a completely reliable non-surgical way of identifying the version [of BIA-ALCL] that’s going to be okay, from the much rarer one that may not be,” he said. “So, the advice to all patients still has to be, if you have the condition, you need, as a minimum, to have the implants and capsule removed to be 100% safe.”

Professor Deva said that increased awareness of BIA-ALCL was important, particularly among GPs.

“Not everyone with a seroma is going to have an ALCL, but certainly if someone has had implants for a period of time and presents with swelling it should really be treated as ALCL until proven otherwise,” he said in an MJA InSight podcast.

Professor Deva is also soon to publish research in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery investigating the role of infection in the development of BIA-ALCL.

“What we have shown over 10 years is that the … commonest cause of contracture and re-operation is actually infection – the interaction of bacteria with these [implant] surfaces,” he said, adding that this infection may play a role in causing inflammation and the transformation of lymphocytes into cancer.

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert

It would seem that a proper search of the literature has not been made .

Textured (Ashley ) prostheses were first used in 1970 & I have published 19 & 21 year follow ups on these prostheses; capsular contracture occurred much later than in smooth wall prostheses. There was only one case of Carcinoma Cholm Williams had only one case of the same disease amongst his patients @ that stage, using smooth prostheses.

A study done @ Emory University had similar results with Ashley prostheses known @ that time as “Meme”.

none