A LANDMARK 25-year study into the baseline rate of microcephaly in Australia has confirmed an important link between the neurological condition and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD).

The study, published in the MJA, was intending to establish a baseline prevalence of microcephaly to ready the country for potential Zika cases.

In addition to establishing a microcephaly prevalence of 1 in 1830 births, the study found that the most frequent cause for microcephaly was FASD, particularly in Aboriginal births.

Professor Carol Bower, director of FASD Research Australia and an author of the article, told MJA InSight: “FASD is clearly quite an important contributor in Australia and particularly in Aboriginal communities. It’s important to diagnose the causes of microcephaly if you’re wanting to monitor a new teratogen like Zika.”

The epidemiological study used the Western Australian Register of Developmental Anomalies (WARDA) to identify births between 1980 and 2015 affected by microcephaly. Complete ascertainment was available for births between 1980 and 2009, where there was a 6-year follow-up.

In that period, 416 cases were identified (5.5 per 10 000 births) and a cause of microcephaly was identified in 186 cases. The prevalence was higher among Aboriginal (21 per 10 000 births) than non-Aboriginal births. The cause was more frequently identified for Aboriginal (70%) versus non-Aboriginal (38%) births and in most cases, the cause in Aboriginal births was FASD (11 per 10 000 births). In comparison, for non-Aboriginal births, the most frequent cause was monogenic disorders (0.68 per 10 000 births).

According to lead author Dr Michele Hansen: “Relative disadvantage in many Aboriginal populations may impact on rates of microcephaly associated with infection or teratogens such as alcohol. However, microcephaly of unknown cause was also higher in Aboriginal births. This may relate to relative lack of access to or engagement with health care services and the paucity of genomic reference data for Aboriginal Australians, leading to delays in the identification of rare genetic diseases, some of which cause microcephaly.”

The authors believed FASD could also be behind many of the unknown causes found in the study.

“We also know FASD is underdiagnosed in Australia, so FASD as a cause of microcephaly is likely higher in both, and it could be underdiagnosed in non-Aboriginal children as well as Aboriginal children,” Professor Bower said.

Underdiagnosis of FASD is an area that experts such as University of Sydney’s Professor Elizabeth Elliot have been working to improve.

“Stigma is a big issue. Sixty percent of paediatricians say that they’re worried about stigmatising families if they make a FASD diagnosis. Others say that they don’t know how to make a diagnosis, and others say that they didn’t know how to treat it or where to go for confirmation.”

Professor Elliot and colleagues have been working on making diagnosing and finding FASD treatment easier, with the launch in 2016 of the Australian guide to the diagnosis of FASD.

It contains the Australian FASD Diagnostic Instrument and information about how to use the instrument, with the aim to facilitate and standardise diagnosis in Australia.

There are a variety of tools to determine a FASD diagnosis, with three main areas of examination:

- Maternal alcohol use and other exposures.

- Neurodevelopmental impairment. Domains of impairment are:

- brain structure and neurology;

- motor skills;

- cognition;

- language;

- academic achievement;

- memory;

- attention;

- executive function, including impulse control and hyperactivity;

- affect regulation; and

- adaptive behaviour, social skills and social communication.

- Facial and other physical features (small palpebral fissures, smooth philtrum and thin upper lip).

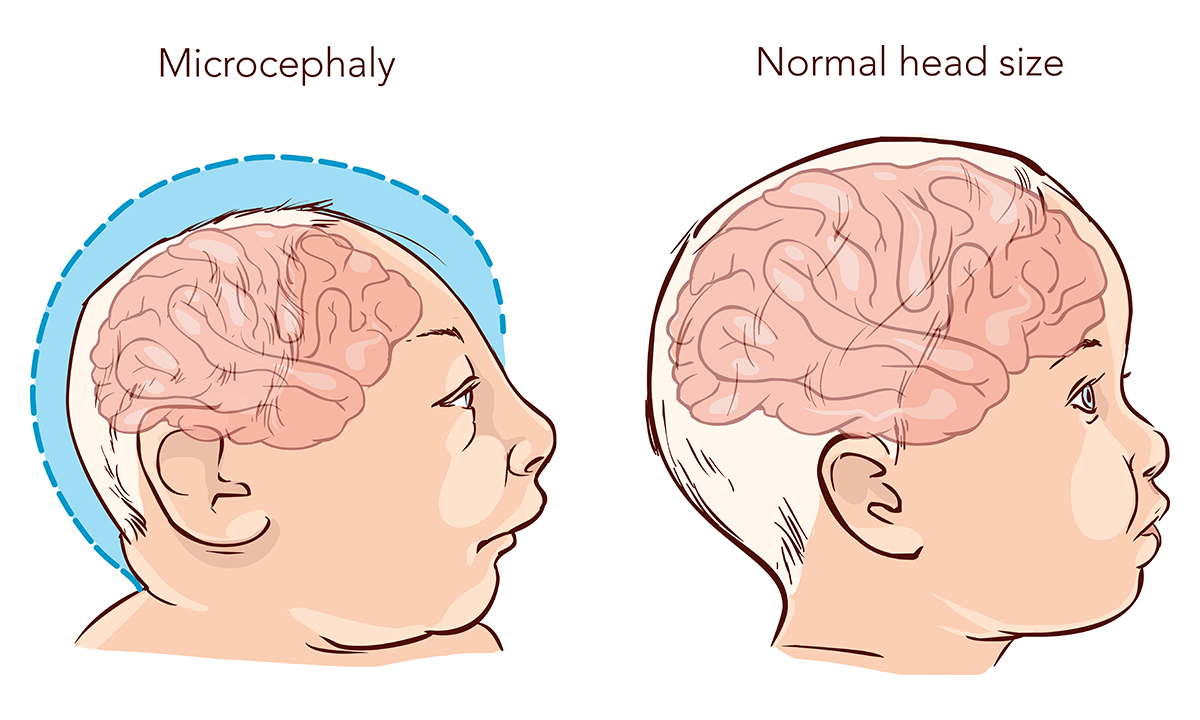

A diagnosis of microcephaly is important when assessing children under 6 years of age, as neurodevelopmental assessment is limited and their brains have capacity for change. Clinicians can diagnose FASD when microcephaly is present if the child also has confirmed or unknown prenatal alcohol exposure and has the three sentinel facial features noted above.

Dr Elliot hoped the study would highlight the importance of measuring head sizes.

“Doctors need to make sure that they measure heads at birth and in childhood, and plot them against the standard charts. If they find a child with microcephaly who is likely to have neurodevelopmental problems, the cause needs to be investigated and they need to think about FASD.”

As a direct result of the study, WARDA will now add head circumference to their register.

There is no universally accepted definition of microcephaly; however, WARDA defines it as an occipito-frontal head circumference below the third percentile or more than two standard deviations below the mean sex- and age-appropriate distribution curve.

Nevertheless, as Dr Hansen explained, many countries have a much stricter definition.

“They only record babies with microcephaly if their head size is less than the first percentile head size and, therefore, they exclude some babies that have neurodevelopmental delays with a larger head size.”

With the addition of head circumference being added, the researchers will be able to compare their results with those that have a stricter definition.

Most importantly, the study provides a baseline for microcephaly in the event that the Zika virus finds its way to Australia.

According to Dr Hansen: “These baseline data were not available in Brazil at the time of the Zika outbreak there and hampered efforts to determine whether the spike in microcephaly cases being reported by clinicians in that country represented a real increase in risk of this defect.

“If there are ever increasing reports of microcephaly in Australia, it will be much easier to compare these rates with the baseline data we have now described.”

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert