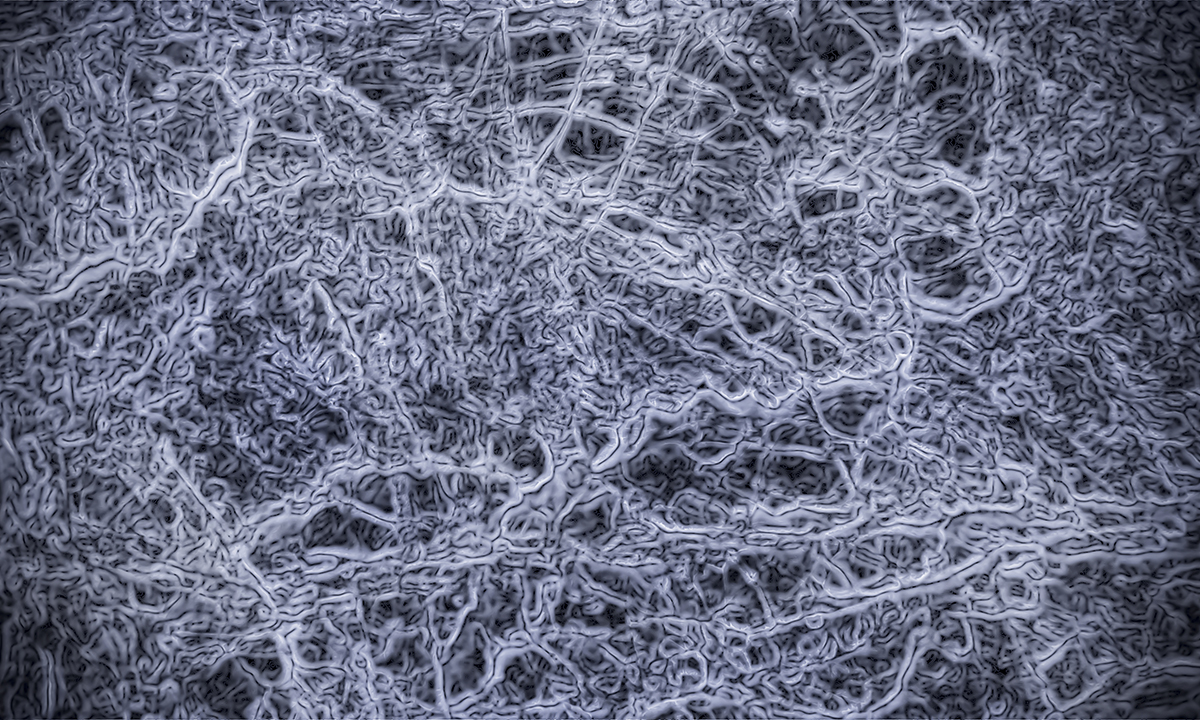

THERE is still much to learn about our gut microbiome, but a leading Australian expert says that now is the time to accelerate research efforts and translate this progress into practice, including faecal microbiota transplants (FMT).

Professor Mark Morrison, chair of microbial biology and metagenomics at the University of Queensland Diamantina Institute, told MJA InSight that “the microbiome is now both measurable and quantifiable in a manner once thought impossible just a few years ago”.

“Clinicians are justifiably cautious but also optimistic of the potential medical benefits from FMT as a treatment option.

“My role as a microbiologist is to support the development of the next generation of microbiota transplants, first by improving our representation of the gut microbiome in a viable state, and then, by providing options to produce rationally designed microbial consortia that can provide a more controlled and personalised inoculum that is ‘clean’, minimises adverse risks and, ideally, improves efficacy.”

Professor Morrison co-authored an article published in the MJA which discussed how new sequencing technologies have advanced our understanding of the human microbiome.

“We have learned that our microbiota ages with us, and can be shaped in a deterministic way by our own genetics and dietary pattern,” the authors wrote.

They wrote that the interactions between microbiome and host could substantially add to our knowledge of the pathophysiology of many diseases; however, these interactions are complex.

Simple measures of exposing patients to stool preparations through FMT might be attractive, but are unlikely to be the way forward considering safety and standardisation concerns.

Genomics-based approaches will be crucial to revealing potential roles for microbiome in health and disease, “and when combined with the principles of environmental microbiology, including culture, offer the opportunity to shine a light on our microbial dark matter and refine the concepts of probiotics, prebiotics and FMT”, the authors wrote.

Professor Morrison said that the microbes that colonise our different body sites are a functional and dynamic interface between our own genetic makeup, our environment and our lifestyle choices.

“I understand that Leroy Hood coined the term ‘P4 medicine’: predictive, preventive, personalised, and participatory. Managing our health via the ‘microbiome’, I think, will be a part of that approach”, he said.

Dr Paul Bertrand, senior lecturer in the school of health and biomedical sciences at RMIT University, told MJA InSight that “for there to be successful translation of this research, we need to know what is a good microbiome that you’re trying to get in a person, and this is probably going to be very individual for each person”.

“You also need to make sure that the treatment has the desired effect to change the microbiome to what you want. You need to make sure it’s going to be stable over time — because most of the changes that have been made, whether they be antibiotics or FMT, aren’t stable over time. They drift back to their old state.”

He said that it crucial that science catch up with FMT so that this approach could be done better than it was currently.

Dr Carly Rosewarne, research scientist at the CSIRO, told MJA InSight that “we know that our gut microbial communities are malleable and are influenced by external factors including diet and lifestyle”.

This means that manipulation of the gut microbiome an attractive target for disease prevention and treatment.

“We need to be careful to navigate the hype. Where mouse models are employed we can control the parameters in order to test different hypotheses, but this also means it may prove difficult to replicate the same findings in humans.

“Many clinical studies are successfully demonstrating strong correlations but it is more challenging to establish causation. It is the classic chicken and egg situation – are the microbiota directing the pathology or vice versa?”

Dr Rosewarne said that it was crucial to make sure that investigations were statistically robust, and not to draw conclusions from studies that were underpowered or had set out to answer the wrong question.

Dr Bertrand said that research progress over the last decade had been rapid and exciting.

“There’s been lots of this genomic-style sequencing of the microbiome, and that’s given us heaps of information. But this hasn’t actually told us what they’re doing. In most cases, we’ve got their names but we have no idea what they do.”

Professor Morrison said that in the future, it could be possible to meaningfully include microbiome assessment, treatment, and monitoring as part of the arsenal of measures and approaches that would contribute to P4 medicine.

“However, success will also be contingent on the further integration and undertaking of microbiome research within a medical and clinical setting, more so than microbiome researchers ‘going it alone’.”

To find a doctor, or a job, to use GP Desktop and Doctors Health, book and track your CPD, and buy textbooks and guidelines, visit doctorportal.

more_vert

more_vert