A SMARTPHONE app linked to a centralised Australian registry of pregnant women who have potentially been exposed to or infected with the Zika virus may be an opportunity to both collect data and keep patients informed and reassured, says an expert in disease surveillance.

Dr Craig Dalton, conjoint senior lecturer at the University of Newcastle’s School of Medicine and Public Health, said such an app and registry combination would be a way of “bringing pregnant women in” to the surveillance process.

“The surveillance function would provide a conduit to a national registry that documents the number of women who have travelled to endemic areas who have been tested for

Zika virus, their laboratory results, pregnancy outcomes, satisfaction with and understanding of information provided,” Dr Dalton said.

“The information provision function would allow pregnant women to receive push notifications of updated official information on Zika virus, including updates on the risk of outcomes and the latest screening protocols.

“This would be ideal given the rapid revisions of screening and counselling protocols.”

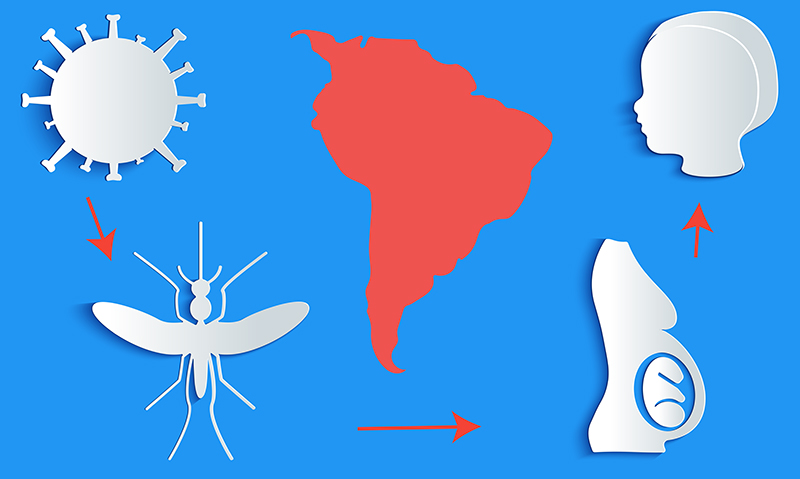

Continuing assessment of the situation in Brazil “appears to confirm” the link between Zika virus infection and microcephaly, Dr Dalton said.

“Increasing recognition of adverse pregnancy outcomes among pregnant travellers to endemic areas and the potential expansion of endemic areas has highlighted the need for enhanced surveillance,” he said.

- Related: MJA InSight — Simmons et al: Zika’s here. What does it mean?

- Related: MJA InSight – Zika and the WHO: lessons learned from Ebola

“The high level of anxiety suffered by pregnant women potentially exposed to Zika virus creates an obligation, and an opportunity, to combine both enhanced surveillance for disease and enhanced provision of information to pregnant women.”

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recently announced a voluntary registry to collect information about American pregnant women with confirmed Zika virus infection and their infants.

“It may be argued that the number of women affected in Australia is too low to justify a central registry,” Dr Dalton said. “However, Zika is likely to be with us for many decades, the endemic areas may expand, and standardised data collected in Australia could contribute to regional or international registries.”

Dr Dalton said that although the central registry would privilege data from the treating obstetrician, experience with Flutracking.net, of which he is director, and Vaxtracker, suggested that inviting women to participate would enhance the utility of the app and registry.

“A combination of both health provider and patient participation would allow validation of one data source against the other and capture-recapture methods could estimate the under-ascertainment of each data source,” he said.

“Registration with unique identification numbers would allow the linking of participant and provider data.”

Issues of privacy and data security should not be a problem “provided standards for secure connection and encryption protocols are followed”, he said.

“Beyond the surveillance benefits of this approach, participatory surveillance empowers highly motivated women to contribute towards their own and others health and wellbeing.”

Dr Dalton is co-convener of the 3rd International Workshop on Participatory Surveillance being held in Newcastle from 22 March.

more_vert

more_vert