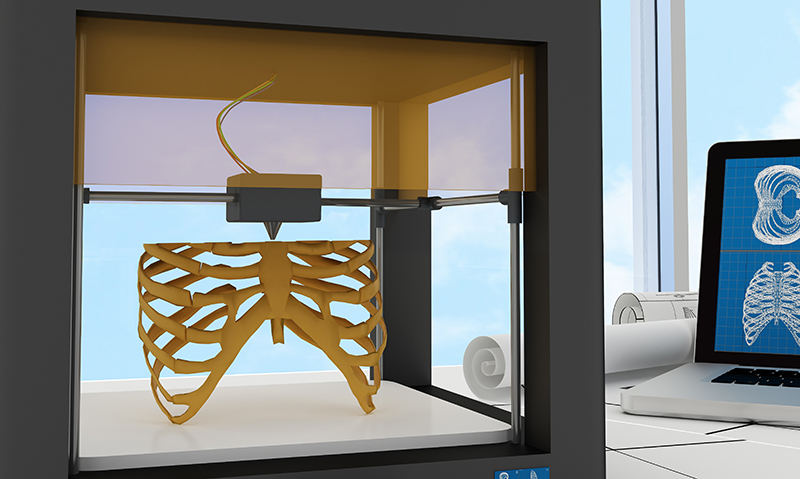

EXPERTS are debating how widely 3D printing should be used in Australia, but they all agree that when the technology is used, it offers big benefits for doctors, patients and the health care system.

Dr George Dimitroulis, an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, told MJA InSight that “the sky is the limit for 3D printing because anything you can design on a computer, you can use”.

In a world first last year, Dr Dimitroulis and his surgical team successfully implanted a titanium 3D-printed prosthetic jaw into patient who was missing his temporomandibular joint.

Dr Dimitroulis designed the prototype prosthesis, which was refined and tested in the mechanical engineering department of the University of Melbourne.

He said that the major benefit of 3D printing was the production of customised implants and components that fitted individual patients perfectly.

“We first started with doing 3D printed joints, but now we’re looking at doing total jaw replacements,” Dr Dimitroulis said.

- Related: MJA — Manufacturing a human heel in titanium via 3D printing

- Related: MJA InSight – Jane McCredie: Reasons to share

Dr Nigel Finch, chairman of health care technology provider 3D Medical, told MJA InSight that the customisation of 3D printing offered a versatility that off-the-shelf implants and components could never achieve.

“Implants generally come in small, medium and large sizes, but we know that patients can come in many different sizes. This means that during surgery, work often has to be done to make their body fit the implant.”

With 3D printing, it’s the implant that accommodates the patient, and this has the potential to make big improvements to the health care system, he said.

“This reduces the time spent in the operating theatre – a 4-hour operation becomes 3 and that saves money.”

Dr Finch said that patients also recover faster when the implant fits them perfectly, which translates into even more cost benefits.

Dr David Ackland, senior lecturer in biomedical engineering at the University of Melbourne, agreed, saying that the customisation of 3D-printed implants is making life easier for doctors.

He told MJA InSight that 3D printing would be particularly helpful for patients who had a joint replacement that needed to be replaced again.

“This replacement revision is nasty and something you never want to see. Patients will need to undergo salvage procedures and the joints might have to be fused together, so 3D printing is a great option for these patients.”

Dr Ackland said that while 3D printing did have scope to become more commonplace in medicine, he did not feel there would be a time in Australia where 3D-printed knees and hips were the norm.

“Every year there’s 10s of thousands of hip and knee replacements, and surgery techniques are already very well established and effective. 3D printing will be used more in the really complex and strange cases.”

However, Dr Finch said that while using 3D printing for these extreme one-off cases was “all well and good”, it meant patients and doctors were not getting the most out of the technology.

“The real benefit will be in moving towards mass customisation where we create ‘consumerable’ items, like electro-beam shields for radiotherapy treatment.”

3D-printed shields are tailored to the patient, which allows the radio beam to pass more precisely into their tumour and spares the healthy tissue.

Dr Finch said that surgeons also stood to gain from the wider adoption of 3D technology, which could significantly enhance their pre-operative planning.

These 3D-printed bio-models map out a patient’s anatomy, providing valuable medical certainty, he said.

“All the detail is there for them – from the patterns of blood flow and vasculature, to the roughness of a bone. You can’t get that level of detail from a 2D image.”

Monash University’s Centre for Human Anatomy Education has a full library of 3D-printed cadavers and body parts which they developed after considering the high costs of plastination, director Professor Paul McMenamin has been quoted as saying.

Dr Dimitroulis said that were clear challenges that needed to be overcome before 3D printing is used more widely in Australian hospitals.

“As with any new technology, there is hesitation, so we want to show how easy 3D printing is. Sometimes it just takes one key player to get on board and then everyone will.”

Dr Finch agreed, but said the real challenge could be on the commercial front.

“We want the health care system to absorb the cost, but we need more evidence before this can happen.”

Dr Finch said research needed to demonstrate the clear benefit of using 3D printing for mass customisation in terms of time and cost savings, and improved patient outcomes.

more_vert

more_vert

A 2016 systematic review by Martelli et al. found that three-dimensional (3D) printing is becoming increasingly important in medicine and especially in surgery. The aim of their study was to identify the advantages and disadvantages of 3D printing applied in surgery.

They conducted a systematic review of articles on 3D printing applications in surgery published between 2005 and 2015 and identified using a PubMed and EMBASE search. Studies dealing with bioprinting, dentistry, and limb prosthesis or those not conducted in a hospital setting were excluded.

A total of 158 studies met their inclusion criteria. Three-dimensional printing was used to produce anatomic models (n = 113, 71.5%), surgical guides and templates (n = 40, 25.3%), implants (n = 15, 9.5%) and moulds (n = 10, 6.3%), and primarily in maxillofacial (n = 79, 50.0%) and orthopaedic (n = 39, 24.7%) operations.

They found that the main advantages reported were the possibilities for preoperative planning (n = 77, 48.7%), the accuracy of the process used (n = 53, 33.5%), and the time saved in the operating room (n = 52, 32.9%); 34 studies (21.5%) stressed that the accuracy was not satisfactory. They found that the time needed to prepare the object (n = 31, 19.6%) and the additional costs (n = 30, 19.0%) wereals seen as important limitations to the routine use of 3D printing.

It was concluded that the additional cost and the time needed to produce devices by current 3D technology still limit its widespread use in hospitals. The development of guidelines to improve the reporting of experience with 3D printing in surgery was seen as highly desirable.