MELBOURNE is not the only place for thunderstorm asthma, and asthmatics aren’t the only ones at risk, warn experts who are calling for a ramp up of asthma management efforts and research to develop a model that can accurately predict when an event will strike.

At least eight people have now died as a result of the thunderstorm asthma event that occurred on 21 November 2016, and according to the Victorian Department of Health, more than 8500 people have presented to emergency departments with respiratory problems.

Dr Michael Sutherland, a respiratory physician at Austin Health and Epworth HealthCare in Victoria, said a trend of particular concern during the Melbourne epidemic was that it didn’t just affect people who knew they had asthma.

“The real worry is for people who have never had an asthma attack before, or people with seasonal asthma that isn’t being treated,” Dr Sutherland told MJA InSight.

“It was conspicuous that the severe long term asthmatics, many of whom are allergic to rye-grass, were not represented in admission statistics, probably because of inhaled steroids, asthma plans, and staying indoors. So, inhaled steroids appear to be protective.”

Dr Sutherland said that in this observation there was also a crucial note for GPs.

“Look carefully for those hay fever sufferers who ‘wheeze and sneeze’ – they should be prescribed preventers, relievers and a springtime asthma management plan.”

Associate Professor Mark Hew, head of allergy, asthma and clinical immunology at Alfred Hospital, told MJA InSight that there were several key mechanisms that came together to trigger thunderstorm asthma attacks.

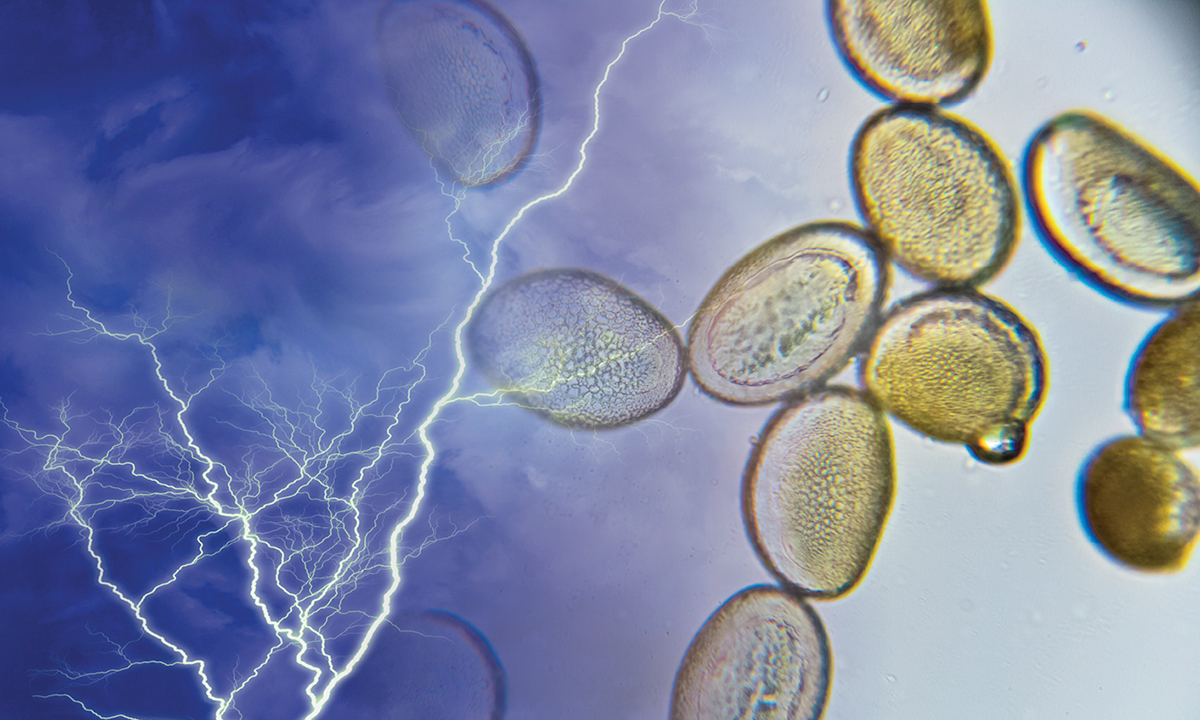

First, he said, high levels of allergen needed to be present. In Melbourne this was grass, but in some cases, mould spores also appear to be problematic.

“Secondly, moisture in the air from the thunderstorm is absorbed by pollen grains by osmotic pressure causing them to burst and release tiny allergen-laden starch granules 3 microns in diameter,” Associate Professor Hew said.

“Thirdly, thunderstorm outflows bring these starch granules down to ground level to be inhaled by susceptible individuals.”.

Dr Steven Lindstrom, respiratory registrar at the Austin Hospital in Melbourne, told MJA InSight that while Melbourne appeared to be a “global hot spot” for thunderstorm asthma, it was not limited to the city and outbreaks had been reported in New South Wales, the UK and Canada.

Professor Helen Reddel, a respiratory physician and research lead at the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, cited the work conducted by Professor Guy Marks on thunderstorm asthma events in Wagga Wagga.

One of the studies, published in 2001, showed that the people most likely to be affected by thunderstorm asthma were those with allergies to rye-grass, and that about a third of them had not had asthma before.

A detailed examination of one of the severe thunderstorm asthma events showed that the arrival of thunderstorm outflow was accompanied by a large increase in the concentration of pollen grains in ambient air.

“Shortly after this occurred, there was the first call to the ambulance,” Professor Reddel told MJA InSight.

As a result of this research, public message alerts reminding people with asthma in the Wagga Wagga region to use their preventer inhaler were now sent out during spring and summer.

“There is also a system set up with the weather bureau to notify local health professionals when there are outflow thunderstorms so they can prepare,” Professor Reddel said.

“So yes, it can be predicted, and what has been done in NSW can be looked at for other states.”

However, Dr Lindstrom said that “at this stage it’s not clear we understand all of the factors that contribute to the ‘perfect storm’ for thunderstorm asthma”.

“Pollen counts, rain forecasts, particular wind patterns and temperature changes are all potential predictive factors, but not all epidemics of acute asthma coincide with thunderstorms, nor is the inverse true. Further research is required.”

Professor Hew agreed, saying that “more work needs to be done to predict the exact combination of factors required for thunderstorm asthma”.

“The Department of Health and Human Services is coordinating activity around prediction, which involves pollen counters and the Bureau of Meteorology to address exactly this issue.”

Dr Lindstrom said that developing an effective predictive model “would allow us to warn potentially affected individuals to stay indoors and have inhalers on hand, alert people to check on friends and family, and allow hospitals and emergency services to pre-emptively allocate resources”.

Professor Reddel said that there were some key lessons to take from the thunderstorm asthma event in Melbourne.

“From the research in Wagga Wagga, we know that people taking preventer inhalers are less likely to come in [for emergency care] on a thunderstorm day.”

Professor Reddel admitted it was difficult to make recommendations, “because we know that not all the people who end up in hospital have had asthma before, some have just had hay fever”.

To that end, she said it was important for research to investigate whether nasal sprays or immunotherapy could work for people with hay fever to prevent thunderstorm asthma.

Dr Sutherland added that based on anecdotal data from Austin Health and HealthCare, “we know that the emergency staff did an amazing job – they enacted disaster plans and treated mass casualties”.

Professor Hew said that hospitals in other areas at risk should now review their protocols for external disasters to ensure that they are prepared for massive increases in patient load.

Dr Lindstrom said that “rallying medical and nursing staff is only part of the required response”.

Creating a room to triage patients, clearing intensive care beds, having educational products on hand, and securing adequate supplies of asthma-relieving medications were further considerations that needed to be managed expeditiously, he said.

Latest news from doctorportal:

- Saliva test could predict lung disease

- Obesity gap widens between country, city

- Could a cannabis pill reduce chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting? Here’s how we find out

- Health Department admits truth on bulk billing

more_vert

more_vert