EXPERTS say Australia’s blood supply is one of the safest in the world and that there is no need to change the screening processes, after a new study revealed a possible link between blood transfusion and an increased risk of liver cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Dr James Daly, president of the Australian and New Zealand Society of Blood Transfusion, told MJA InSight that “regardless of the apparent association of transfusion and cancer inferred from this study, there are many patients who receive repeated blood transfusions over many years from childhood”.

“If there was a true and significant carcinogenic factor directly associated with transfusion, I would expect this would have been identified in this transfusion dependent population.”

The UK research, published in the Annals of Oncology, included 1.3 million women enrolled in the Million Women Study. The women were recruited in 1998, on average, and were followed for hospital records of blood transfusions and for cancer registrations. Women with known possible pre-cancerous conditions before or at the time of transfusion were excluded, and the authors adjusted for potential confounding factors.

The authors found that during follow-up, 11 274 women had a first recorded transfusion in 2000 or after, and 14.6% of them were subsequently diagnosed with cancer after the transfusion. Five or more years after blood transfusion, the only significantly increased risks were for liver cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It was noted that women with a record of blood transfusion were older at baseline, and were more likely to come from the most deprived tertile of the population, be a current smoker, have greater body mass index and drink less alcohol than women without a transfusion record.

The authors acknowledged that “blood transfusions are for life-threatening situations, and the immediate benefits would outweigh the long term risk of cancer”. However, they said that the increase in cancer risk after transfusion “warrants investigation of carcinogenic agents not currently screened for that are still being transmitted by blood transfusion”.

Professor James Isbister, consultant haematologist and clinical professor of medicine at the University of Sydney, told MJA InSight that this was a “unique” piece of research. “In many ways, the authors have actually underdone their case – it could have been strengthened.”

He said that in particular, the explanation for the association should have gone further.

“Firstly, there is plausibility that a transfusion could give a patient a virus. Then there’s also a good mechanism explanation behind it – that a virus can cause cancer.”

Dr Joanne Pink, chief medical officer of the Australian Red Cross Blood Service (ARCBS), said that the findings were interesting; “however, the study had a number of limitations and for this reason, it is not possible or appropriate to conclude that transfusion causes an increase in cancer risk”.

“The study is subject to bias and confounding. For example, researchers did not have access to information on the type of transfusions, the amount of transfusions and whether there were unrecorded transfusions, nor did they have access to comprehensive medical records,” Dr Pink told MJA InSight.

Dr Daly said a major problem with the research was the study design.

“While [the authors] have tried to adjust for various known risk factors for cancer, they cannot possibly control for all known and unknown risks, many of which may be much more likely to be carcinogenic than blood transfusion.

“It’s the common mistake of a correlation being misinterpreted as causation.

“Consequently, it is not sensible, or even possible, to alter the current screening of blood donors in Australia based on this study,” Dr Daly said.

Dr Pink agreed, adding that “we will certainly keep an eye on further research in this space, but for now no change is required to blood service donor eligibility criteria or screening, nor in clinical practice around transfusion”.

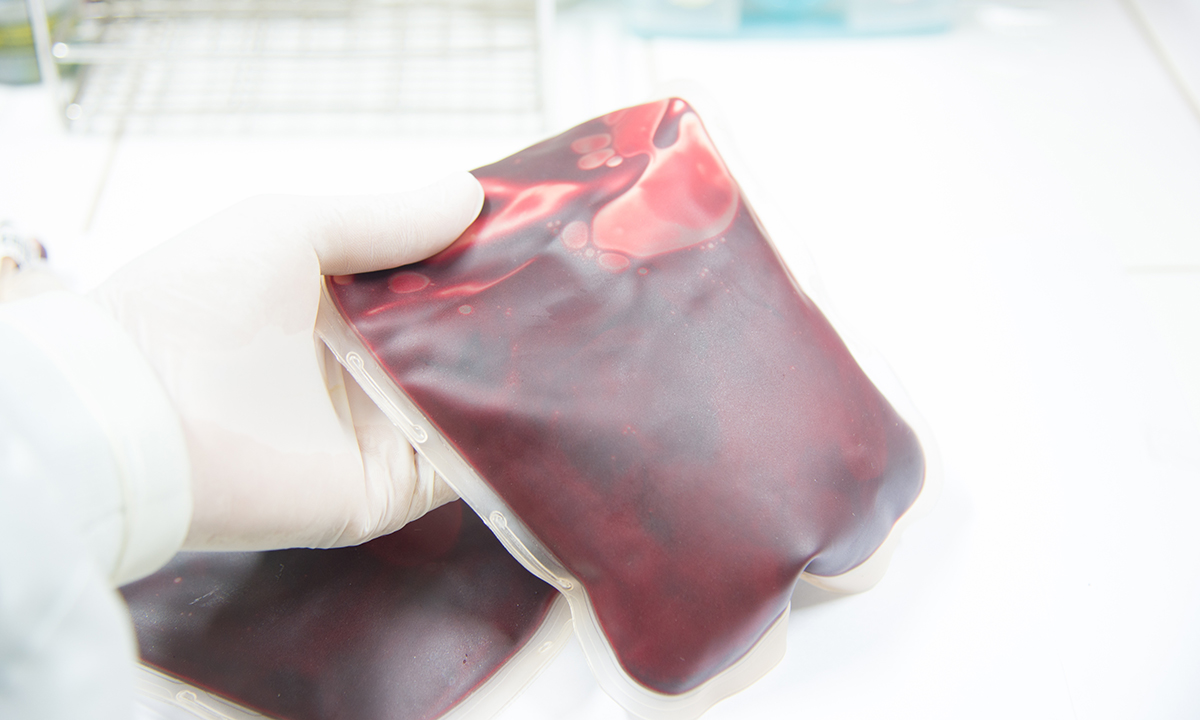

“Australia has one of the world’s safest blood supplies. We collect 1.3 million donations every year that go towards saving the lives of many thousands of Australian patients,” she said.

Dr Daly said that the ARCBS screened all donors with a pre-donation health questionnaire, and all donations were tested for HIV, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus by serology and nucleic acid testing, along with additional testing for syphilis, human T-lymphotropic virus, cytomegalovirus and malaria depending on donor or patient characteristics.

He said it was true that Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and hepatitis G were not routinely screened for in blood donors in Australia, or anywhere else in the world.

“However, from what we know about these viruses, it seems unlikely that they could explain the observed association in this study.”

Dr Daly said that EBV infection was ubiquitous throughout the world, and most people had been exposed to the virus by adulthood, making it doubtful that the transfusion of EBV could explain the association observed in the study.

“Hepatitis G virus infection is less common than EBV in the general population, but still several times more common than the incidence of transfusion in this study,” he said.

Professor Isbister said that a key point to take from the paper was the importance of focusing on patient blood management to reduce the need for transfusions.

“In Australia, we’re lucky, we’ve got national blood patient management guidelines which the rest of the world has looked to, and we’ve done some of the best studies [in this area], particularly in Western Australia.

“The real message is that this study provides more evidence for the precautionary principle of blood transfusion,” Professor Isbister said.

This principle underpins Australia’s patient blood management guidelines which describe a range of medical and surgical strategies that aim to conserve and optimise a patient’s own blood. As a result of this type of management, patients usually require fewer transfusions of donated blood, thus reducing transfusion-associated complications.

Latest news from doctorportal:

- AMA, Govt hold talks on ‘more balanced’ approach to pathology rents

- Worrying MBS changes could be more than skin deep

- Blood clots more likely with testosterone

- Women don’t always get what they want from labiaplasty

more_vert

more_vert

I refused to have any blood transfusions when first diagnosed with multiple Sclerosis and mgus suspected multiple myeloma in case the blood products were contaminated. For that reason I refused radiation therapy and chemotherapy . Myeloma patients usually need blood transfusions but that was a risk I wouldn’t take and no I am not a Jehovah’s witness either.

A large observational study with a couple of ‘associations’ noted. Interesting but certainly not alarming.

We know that a significant population (1 to 2%) of people have a very low but detectable level of CD5+ve clonal B cells by the age of 40 ( which would not have been screened for) so initial gating in this group may be an issue.

It also would have been interesting to see if there were any other associations present in this group such as death or injury by traffic accidents, star sign or even sunspot activity over the time period associated with or without Spanish summer holidays.