A NEW melanoma therapy carrying genetically modified herpes simplex virus type 1 is now available in Australia, and experts have welcomed the drug as a new weapon against the disease, which offers genuine hope to patients.

The therapy, known as talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), was recently approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for use following the completion of a phase 3 clinical trial.

Rodney Sinclair, professor of medicine at the University of Melbourne and director of dermatology at Epworth Hospital, told MJA InSight that any cynicism towards this particular treatment was misplaced.

“This is not a ‘me too’ drug. It is in essence the first ever melanoma vaccine,” he told MJA InSight.

“Melanoma is a terrible disease; it cripples people in lots of exquisite ways. Hopefully, [talimogene] is the first drug in a new class of therapeutic modalities.”

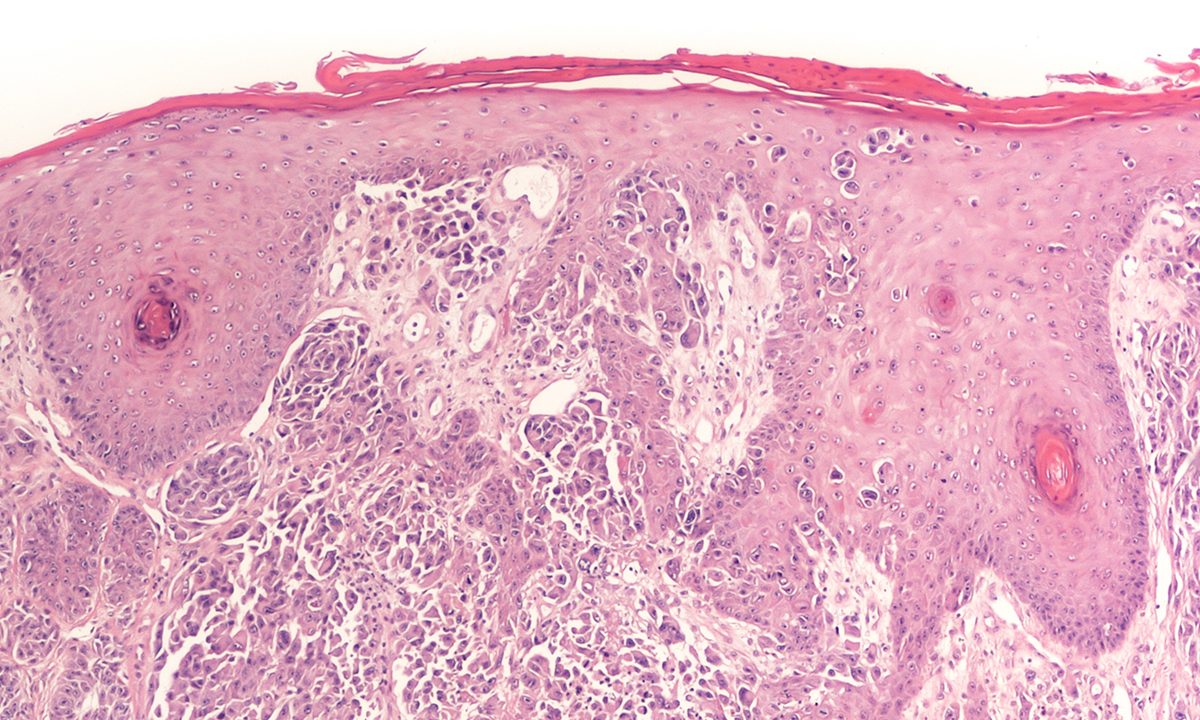

Talimogene is an oncolytic immunotherapy indicated for the treatment of cutaneous, subcutaneous and nodal melanoma lesions that cannot be surgically removed. The vaccine is injected into each lesion and the modified virus then replicates within the melanoma cells and kills them.

The randomised, open-label phase 3 trial of intralesional talimogene compared with subcutaneous granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), sponsored by Amgen, was conducted across 64 centres in the US, UK, Canada and South Africa, and included 436 patients with injectable melanoma that could not be surgically resected.

The researchers found that T-VEC was well tolerated by patients and resulted in a higher durable response rate and longer median overall survival than in the GM-CSF arm, particularly in untreated patients or those with stage IIB, IIC or IVM1a disease.

“T-VEC represents a novel potential new treatment option for patients with injectable melanoma and limited visceral disease,” they wrote.

Georgina Long, professor of melanoma medical oncology and translational research at the Melanoma Institute of Australia, told MJA InSight that “talimogene is a very interesting molecule”.

“This treatment is a great hope for the future – the fact that you can genetically modify a virus to replicate in cancer cells is exciting [and] trials have shown that it does prolong survival.”

Professor Long said that rather than being a therapy for end-stage cancer, “it’s something to supplement other immunotherapies and can be used for low volume metastatic melanoma”.

Professor Sinclair said that the treatment process involved injecting the vaccine into each lesion at week 0 and week 3, and then every 2 weeks.

“The median time to response is 4 months. During this time, half of the injected tumours will have grown 25% in size, before they ultimately regress.”

In the US, the drug is currently priced at $65 000 per patient. Professor Sinclair said that at this cost, the TGA had restricted its use to a very limited patient subset in whom the cost was likely to be economic, namely patients with stage IIIB, IIC and IVM1a disease.

Along with using the therapy to treat in-transit cutaneous and subcutaneous metastasis, Professor Sinclair said that talimogene could be used as a neoadjuvant therapy to shrink a big lesion so that it could be cut out. Talimogene could also be used to treat a solitary skin, subcutaneous or lymph node metastasis.

Adverse side effects to talimogene were reported in the phase 3 trial – the most common of which were fatigue, chills, pyrexia, nausea and flu-like illness.

However, Professor Sinclair said that it was important to consider the side effects in relation to the “miseries” metastatic melanoma inflicted on patients, citing the example of former AFL player Jim Stynes, who died from the disease in 2012.

“If you look back to Jim Stynes, he kept going in to hospital where he would get 10–20 [metastases] removed each time. If you’ve got to keep going for this surgery, it gets harder and harder, whereas if you just need an injection, it’s easier.”

Professor Long said that while talimogene was “not a panacea” and that more work was still needed, it was an encouraging treatment because “it’s thinking outside the box”.

“Melanoma research has steered away from chemotherapy – melanoma has never been responsive to chemotherapy.”

Professor Long said that melanoma research had been pushing in two key directions.

“The first is looking at how we can leverage the immune system. We have been using checkpoint inhibitors, but now we’re looking at other ways of harnessing the immune system.”

The second area of research had been on developing targeted therapies for melanoma, including BRAF inhibitors, he said.

Professor Sinclair said that “what we’re doing is pushing back survival – the median time to death from metastasis was 9 months, now we’ve pushed it to 3–4 years”.

He said the experience had been similar to the early years of HIV, when the goal was to get patients to survive long enough so that they could receive new therapies as they were developed.

Professor Long said that around one-third of patients with advanced melanoma now survived 5 years after diagnosis, “and I wouldn’t be surprised if it gets to 50%”.

Latest news from doctorportal:

- Autism diagnoses leap 10 percent in a year

- A sugary drinks tax could recoup some of the costs of obesity while preventing it

- Sugar tax report met with sour opposition

- Four dead in Victoria asthma crisis after storm

more_vert

more_vert

First developed in Newcastle and usong a coxackie virus a phase 3 trial used in combination therapy is getting brilliant results

http://us2.campaign-archive2.com/?u=7ef2e0d9ae921fe5e6cda7221&id=641651189d&e=11e39a8d35

Although this drug presents a new way to treat melanoma, and the adverse effects are mild compared to some of the systemic melanoma treatments, the comment fails to mention that it’s efficacy is limited. In the main trial only 1 in 6 people (approx. 16%) given the drug had a durable response.

Reading this comment made me wonder who Charlotte Mitchell is – doctor, journalist, pharma rep? There is no affiliation after her name.