NEW prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing guidelines will reduce the uncertainty around testing for many GPs, but experts say consultations with men considering testing will still be complex.

Professor Chris Del Mar, professor of public health at Bond University, said the guidelines were a “major step forward” in providing a united position on PSA testing in Australia.

“There is a harmonisation between the recommendations from lots of different groups in Australia, we’ve got the pathologists, the urologists, oncologists, GPs, public health people all contributing to one guideline,” said Professor Del Mar, who represented the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners on the guidelines committee.

Even with the guidelines, he said consultations with patients to discuss PSA testing would still be complex. He said the balance of benefits versus harms would be determined by a patient’s values, rather than their demography.

“There is no one-size-fits all for this kind of [consultation]. You can’t just say, yep we recommend it. It will be good for some people, and bad for some people who are otherwise demographically identical – just depending on their values,” Professor Del Mar told MJA InSight.

- Related: MJA Research — “What should happen before asymptomatic men decide whether or not to have a PSA test?” A report on three community juries

- Related: MJA InSight — PSA test decline

The guidelines – developed by the Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia in partnership with the Cancer Council of Australia and a multidisciplinary expert advisory panel – were approved and launched last month by the National Health and Medical Research Council. They come after many years of uncertainty with various groups’ guidelines providing sometimes conflicting advice.

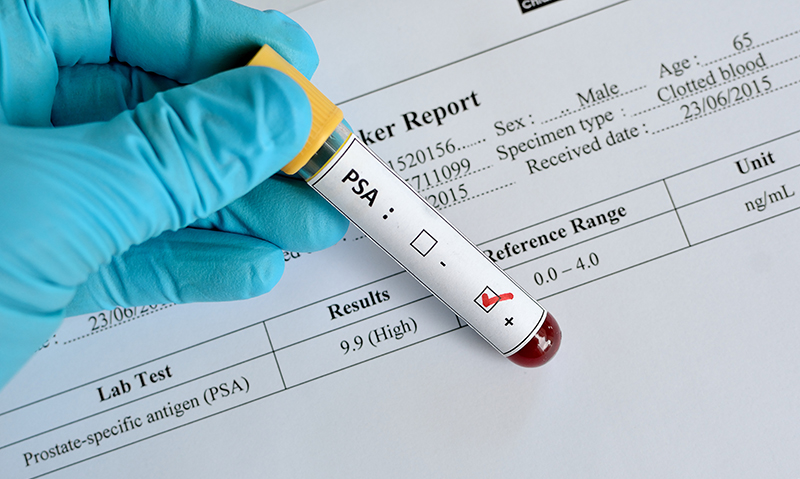

A qualitative study of 32 Australian GPs’ approach to PSA testing, published in BMJ Open last year, found that uncertainty around PSA testing created a “personal burden” for some GPs. The guidelines do not recommend a national screening approach to prostate cancer. They advise that men at average risk of prostate cancer who have been informed of the benefits and harms of testing and who decide to undergo regular testing should be offered PSA testing every 2 years from age 50 to 69. Further investigation should be offered if the total PSA concentration is greater than 3 ng/mL, the guidelines recommend.

It’s also recommended that men in higher risk groups who have been advised of the benefits and harms of testing and wish to undergo regular testing, commence biennial screening from younger ages.

The guidelines recommended against testing in men aged 70 and older, and in those who were unlikely to live for more than 7 years after testing, because in these cases the harms were likely to outweigh the benefits. The guidelines also advised against digital rectal examinations as routine additions to PSA testing in primary care.

The document also covers issues such as active surveillance and watchful waiting.

Professor Del Mar said the new guidelines should raise an alarm for any GPs who order PSA testing without patient consent.

“We have some data that shows that quite a lot of people were having prostate cancer tests done amongst a battery of other tests – the patients didn’t even know they were having those tests done. That’s now verging on the malpractice end of the spectrum. To actually order a test without discussing it with the patient first is definitely bad practice and these guidelines emphasise that.”

Professor Del Mar told MJA InSight that PSA testing had long been an issue in general practice, partly because the recommendations seemed counterintuitive.

“We’re brought up with the notion that ‘a stitch in time, saves nine’, and therefore diagnosing cancer early must be better,” Professor Del Mar said. “So it comes as a surprise that there are some situations in which diagnosing early can cause harm.”

Associate Professor David Smith, associate professor in epidemiology and research fellow at the Cancer Council NSW, said the guidelines would provide a clearer roadmap for GPs in their discussions with men about PSA testing.

However, the decision on whether or not to undergo testing would still present considerable difficulty for men.

“These guidelines will go some way to resolving some of those issues for GPs, but for men themselves, it’s still a very vexed issue.”

- Related: MJA Research — Risk assessment to guide prostate cancer screening decisions: a cost-effectiveness analysis

- Related: MJA Perspective — Should we screen for prostate cancer? A re-examination of the evidence

- Related: MJA InSight — Michael Gliksman: The PSA paradox

Professor Smith said a decision aid for patients was under development, and this was much needed. The decision aid is being developed by the Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia and Cancer Council Australia.

He said the guidelines would provide some assistance to GPs in explaining to men the role of active surveillance for low-risk disease.

“But active surveillance doesn’t come without its issues both in terms of repeated testing and monitoring, and psychological issues of having cancer but not doing anything about it,” he said.

Professor Paul de Souza, foundation professor of medical oncology at Western Sydney University, said the guidelines were extensive and evidence-based, but agreed that discussions with men around PSA testing would remain difficult.

Professor de Souza also noted the recommendation that the harms of testing may outweigh the benefits in men aged 70 and older, on the basis that men would have to live 7 years or more to derive benefit.

“Seventy is not old anymore,” he said. “There would be a reasonable proportion of men who would have a 15-year life expectation on reaching that age. So if you have a 71-year-old sitting in front of you saying ‘I want a PSA test’ … it’s going to be a challenging situation.”

more_vert

more_vert