PRIMARY prevention is the best way to tackle the risk of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) in some parts of rural Australia, say a team of northern Queensland experts, who have highlighted the many diagnostic, treatment and logistical challenges in managing the exceedingly rare but almost always fatal disease.

In a narrative review published online by the MJA, the authors described two confirmed cases and one probable case of the disease – caused by infection with Naegleria fowleri – in young children from remote cattle stations in the same area of central Queensland, who presented to Townsville Hospital between 2001 and 2015.

The infection was confirmed in an 18-month-old girl who presented to the hospital in 2009 with fever, seizures and an altered level of consciousness. The girl died within 72 hours of presentation, and N. fowleri infection was confirmed. The infant’s older sibling had died of an undifferentiated meningitic illness 8 years before, which was retrospectively suspected to have also been PAM.

The most recent case was in early 2015, when a 12-month-old boy was referred to Townsville Hospital after presenting to a local rural hospital with fever, rhinorrhoea and frequent emesis after having a tonic–clonic seizure. On arrival in Townsville, he was increasingly febrile and had developed a maculopapular rash. Although meningitis was initially suspected, it was later confirmed to be PAM.

All three children lived on properties that used untreated bore water.

Dr Steven Donohue, co-author of the review and director of the Townsville Public Health Unit, said that there were initial concerns about a cluster with the presentation of two, possibly three, cases in a small population over a reasonably short time period.

“We were very worried at the time that there could be something else going on that was leading to a cluster. That’s why we investigated it aggressively,” Dr Donohue told MJA InSight. The investigation determined the cause of the cases as N. fowleri infection.

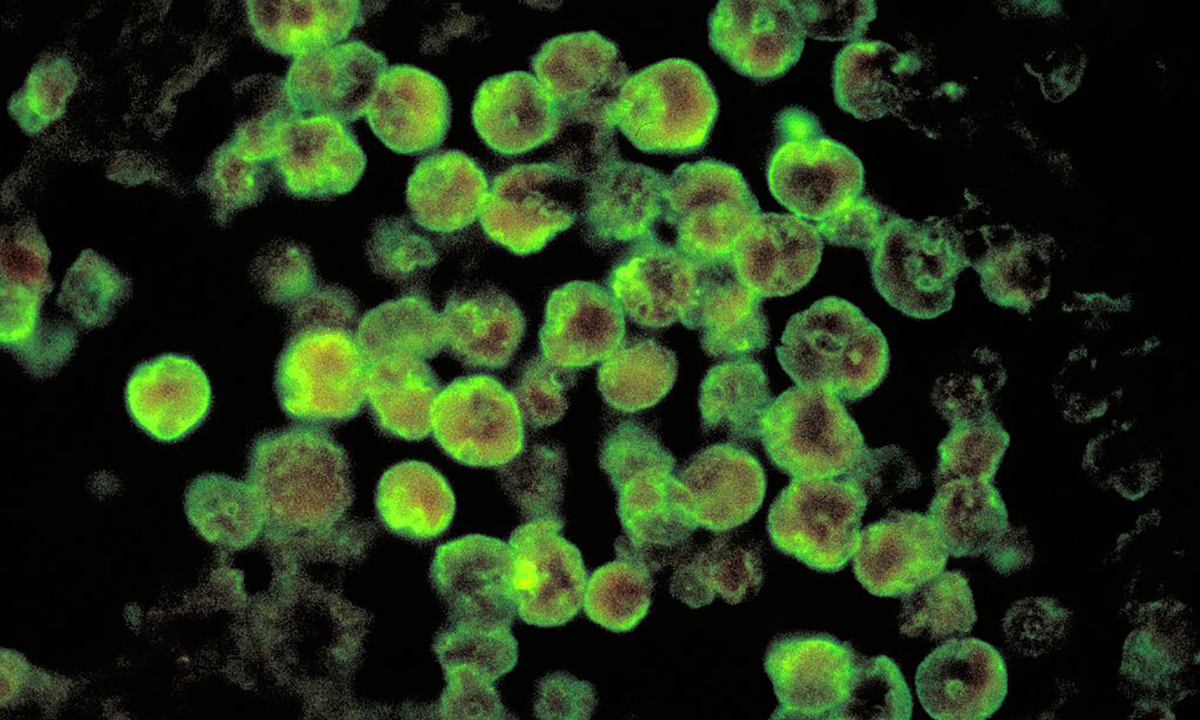

N. fowleri is a thermophilic, free-living amoeba that is commonly found in fresh water that is consistently between 25°C and 40°C. Infection, however, is extremely rare with only about 20 cases confirmed in Australia. Infection occurs when contaminated water is flushed into the nose and the amoeba penetrates the central nervous system via the cribriform plate.

In the wake of the most recent cases, the Queensland Health Department embarked on a public health campaign to raise awareness among rural health practitioners, and promote prevention in the community by stressing the importance of domestic water filtration and treatment.

Dr Donohue said that although the disease was “incredibly rare”, a public health campaign was justified because water treatment could prevent not only PAM, but several other gastrointestinal diseases.

“Some of these outback communities have always been really proud of their water, because it’s so clear. It comes out hot, but it’s lovely to drink and they have never even considered that they might need to purify their water,” Dr Donohue said, adding that modern plumbing had increased water pressure as well as the potential risk of this infection, particularly in children engaging in water play.

He noted that some small Queensland towns also did not have treated water supplies, and it was hoped that greater awareness would expedite plans to address this.

Dr Donohue said that while efforts to improve diagnosis and treatment were important, raising awareness of simple prevention measures was likely to have the greatest impact.

“Clinically, it looks like the much more common bacterial or viral meningitis, and even if you were to detect it early, the outcome is still very poor,” he said. “That’s why, from a public health point of view, I am very keen to do what we can in terms of prevention. Just detecting cases is not going to decrease the death rate. If we want to reduce this problem we need to do more about prevention.”

Dr Patrick Harris, an infectious diseases physician and medical microbiologist at Pathology Queensland and the University of Queensland’s Centre for Clinical Research, agreed that it was important to raise the awareness of the disease among health professionals and in potentially affected communities.

“It’s difficult striking a balance between the rarity of the disease with the dire outcomes when people get infected,” said Dr Harris, who was involved in the treatment of the first confirmed case at Townsville Hospital.

However, he said, the fact that two cases occurred in one family illustrated why prevention and awareness were crucial.

“At the time [of the first case], it became apparent that a sibling had died from a similar illness years earlier. Although we could not prove this, we were fairly convinced that it probably was the same thing,” he said. “Had we known about it at that time, there may have been something that could have been done to help prevent any further cases within that family.”

Dr Harris said it was likely that many cases went undetected in developing countries, but perhaps also in Australia.

Dr Harris said that wider awareness would help promote prevention efforts and improve detection.

“Awareness is going to be one of the keys in trying to tackle this problem, but I don’t think it will go away any time soon, unfortunately.”

Professor Cheryl Jones, President of the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases (ASID), said: “With summer approaching it is vitally important that doctors and communities be aware of PAM and respond immediately to any suspected infections by alerting their laboratories to look for amoebae. Any acutely unwell child with a history of bore water exposure and signs of meningitis or encephalitis should be considered for PAM as a potentially life-threatening diagnosis.

“Families should avoid swimming or diving into warm fresh water or hold their nose if this can’t be avoided.”

Latest news from doctorportal:

- Mental health rates worse in the bush

- Superbugs could be ‘worse than global financial crisis’: World Bank

- ‘Ban this rubbish’: antivax film trashed

- No link between ‘obesity gene’ and ability to lose weight

more_vert

more_vert