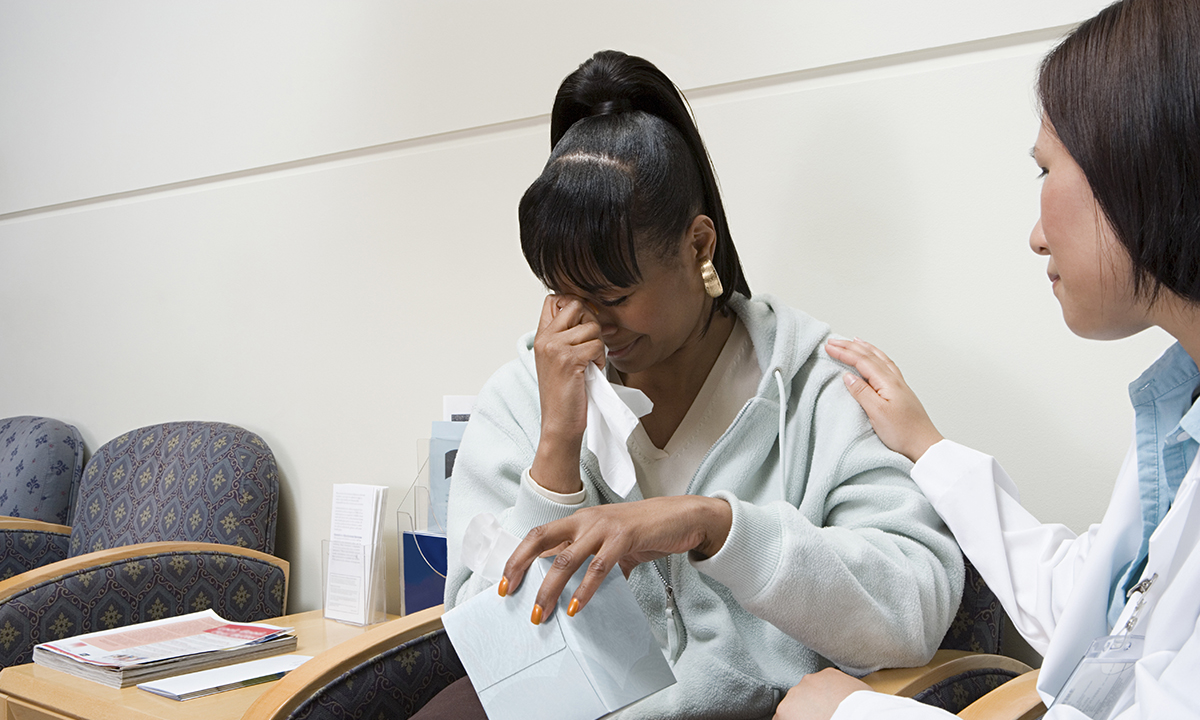

TALKING to patients about abuse can be like opening Pandora’s box, which is why experts are calling for integrated trauma-informed education to guide doctors in what questions they need to ask, and how to manage the answers they may get.

Dr Gabrielle Matta, psychiatry registrar at St Vincent’s Mental Health in Melbourne, told MJA InSight that within current medical courses “there is an overall lack of recognition of the impact a history of trauma can have on a person”.

She said that “students are already given templates about how to talk to patients about sexual health, for example, and this could be expanded on to cover trauma”.

Dr Matta co-authored a Perspectives article published today in the MJA which highlighted the importance of establishing trauma-informed medical education.

“Many doctors lack confidence and remain ill-informed or avoidant when dealing with patients’ psychological trauma” and this can negatively impact both the patient and the health care system. “[While] trauma is an everyday part of clinical discourse within … psychiatry rotations … trauma-informed education is relevant to all clinical specialities,” the authors wrote.

They called for new lines of educational research to guide curriculum design and build on the small body of work already available.

“It is likely that if doctors of all kinds have the knowledge, skills and attitudes to deal competently with abuse and trauma, we can expect improvements in patient care and health service costs, and in the health and wellbeing of medical practitioners,” the authors wrote.

Co-author and Associate Professor Michael Salzberg, psychiatrist at St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, told MJA InSight that “there is a crucial importance in experiential, small group teaching about how abuse affects our clinical practice – and this is not widely done”.

“We have gotten into this silo situation in trauma research, where particular topics get more developed than others.

“What we need is an integrated vision, where all medical educators learn from people who have done this type of work in different types of trauma – whether it be veterans, childhood abuse or elder abuse.”

Dr Simon Rosenbaum, lecturer at the University of New South Wales agreed, saying that a “holistic” approach to both trauma education and research was needed, not just components which focused on individual categories of trauma.

He said that establishing integrated, trauma-informed teaching would recognise that trauma is a reality.

“It’s such an important part of practice. Doctors are going to come across all different types of trauma,” Dr Rosenbaum said.

Dr Louise Stone, GP and conjoint senior lecturer at the Australian National University medical school, said there was there was a place for introducing more trauma-informed care concepts in mental health skills training.

She said that in the current system, it’s not even obvious which psychiatrists are specialised in providing trauma-informed care, and it’s still hard for patients to access public mental health care. “We also can’t expect GPs to open up Pandora’s box when they are stretched for time.”

Dr Stone said that together, these were “structural inhibitors” in the system that needed to be addressed to improve trauma care.

“We need to make a good pathway possible, if not, we’re opening up a ‘can of worms’ that GPs can’t deal with.”

Professor Salzberg emphasised that across all types of abuse, the GP must play an essential and ongoing role in helping the patient.

“It’s not good for a doctor to just handball trauma to a social worker, because that can be threatening. Yes, there has to be a social worker, but there needs to be an ongoing conversation with the doctor about it.”

Professor Salzberg said that students were already getting trained in generic communications skills, but when it came to talking about abuse, there were specific things to do.

“If you ask a screening question, the person may be upset, and you need to be able to deal with that. So it’s not just generic communication skills that are needed, but an understanding.”

Dr Matta said that talking about domestic violence had become easier in recent years.

“It’s become more prominent in the public eye, especially when Rosie Batty became the Australian of the Year,” she said.

Professor Salzberg said that when it came to domestic violence, “more doctors are aware, they know about mandatory reporting and the relevant services available”.

He added that childhood abuse was “unequivocally” already a part of medical education.

“All students do paediatric rotations, and it’s pretty universal that they are exposed to issues around reporting abuse, and what constitutes a suspicious trauma.

“So that’s happening – as it should be. Paediatric abuse is already embedded and this could be built on with other types of trauma and abuse.”

However, Dr Stone said that childhood abuse was still particularly difficult to navigate for a GP.

“Childhood abuse is something that terrifies GPs. They worry they will retraumatise patients and open up stuff they don’t know how to deal with.

“They are traumatised, too, by being unable to help. They may have notified [abuse] in the past, but that notification didn’t translate into action.”

Dr Stone said that “it’s dangerous to say we can solve a problem by just saying that GPs need to be more aware. We need a pathway that actually helps, because the current pathway is uneven.”

Latest from doctorportal:

- LIME Network wins award for promotion of Indigenous health

- Australia’s Health 2016 report card: experts respond

- Pharmaceutical companies targeting nurses

- New strains of norovirus affect thousands of Australians

more_vert

more_vert