AUSTRALIA has lost focus when it comes to familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH), as a leading expert called for a renewal of awareness among health professionals and the introduction of a Medicare item number for obtaining a full family history from patients.

FH specialist and clinical associate professor at the University of Sydney School of Medicine, David Sullivan, told MJA InSight that “we’re doing less well than we used to be doing in FH”.

“Twenty to 30 years ago, young people with FH would present with cardiovascular events. Young families would come in to visit these young patients in hospital, and people would see this and ask ‘what can we do about this?’

“We would like to regenerate this awareness of FH at the acute presentation level.”

Associate Professor Sullivan was commenting on a narrative review, published today in the MJA, which discussed progress in the management of familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH).

FH is currently the most common autosomal dominant condition, and recent evidence suggests that the prevalence of FH has increased from one in 500 people to between one in 200 and one in 350 people. This equates to over 30 million people worldwide.

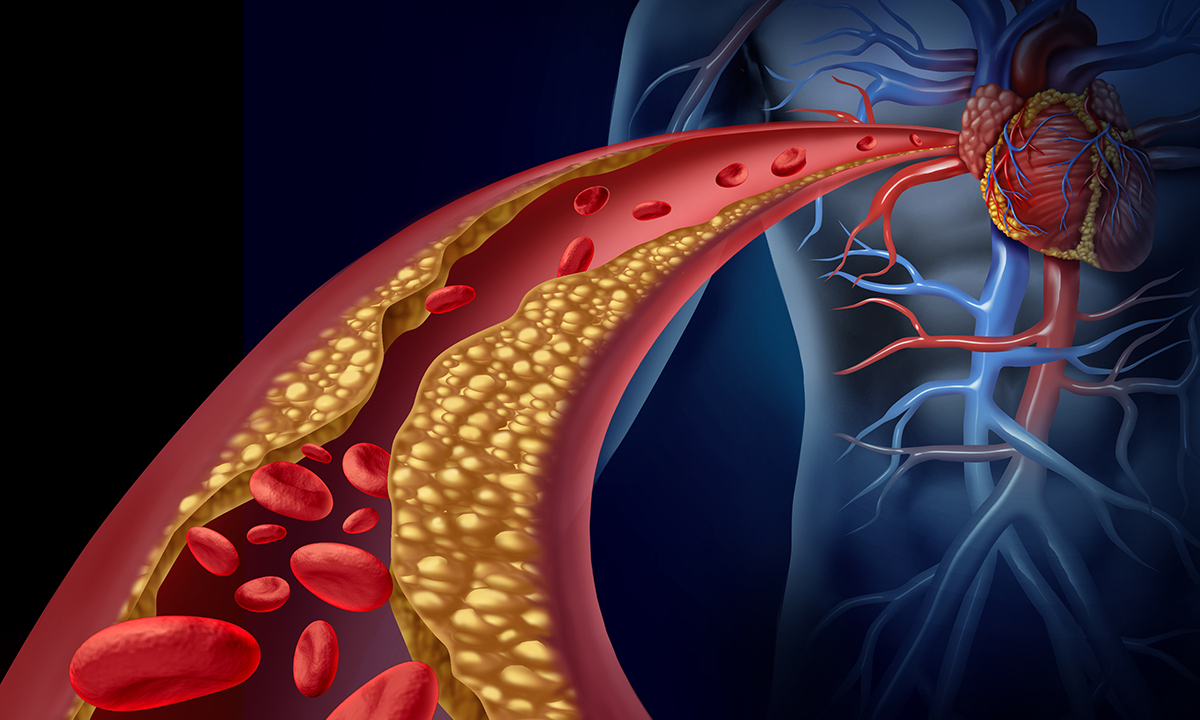

If left untreated, FH can lead to premature coronary diseases. Despite this, most people with FH go undiagnosed, making FH a significant public health challenge.

The authors of the review wrote that “childhood is the optimal period for detecting FH, since low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) concentrations better differentiate affected from unaffected individuals.”

In the Australian community, over 70% of adults with an LDL-c level of 6.5 mmol/L or more have clinical FH, and of these, 30% have a detectable mutation.

“The past 2 years have also seen the development of new treatments for FH, but lifestyle modifications and statins remain the cornerstones of therapy for FH,” the authors wrote.

Professor Anthony Dart, director of the Heart Centre at Alfred Health in Melbourne, told MJA InSight that the cost of new treatments for FH was a significant barrier, with certain treatments amounting to over $10 000 per year.

“Clearly, there needs to be close targeting when it comes to who gets the treatment.”

The review authors wrote that “genetic testing is cost-effective in the cascade screening setting … [however] only a few centres in Australia have this facility and testing is currently not Medicare rebatable.”

They further state that “the onus rests on all health care professionals to improve the care of families with FH, in order to save lives, relieve suffering and reduce health care expenditure”.

“Future research should focus on better approaches for detecting FH in the young and on enhancing the integration of care between GPs and specialists,” they concluded.

Associate Professor Sullivan said that “GPs are very busy, and there’s been very little encouragement to pay attention to family history”.

“Substantial time should be dedicated to this. I do wonder if there shouldn’t be a Medicare item for getting a detailed family history.”

Professor Dart said that GPs have probably not received enough training in the criteria for investigating FH.

However, he added that in practice, it did not have to be a complicated process. If a GP finds that a patient has high LDL-c level, off or on treatment, and has a family history of disease, then that warranted an investigation for FH.

“As recommended in this review, you could then do cascade screening, or the GP could simply advise the patient [about FH].”

Associate Professor Sullivan said that setting up an FH registry, as recommended in the review, would be easy to do.

“This is a significant health problem and it does lend itself to a registry, but people are going to ask that cost-effectiveness question.”

Associate Professor Sullivan said that there was also the potential to improve communication between GPs and specialists.

“We’re developing health care pathways to address this … but we’re lucky if we can get one specialist risk clinic per capital city in Australia.”

Professor Dart said that it was important to consider FH within the broader context of the cardiovascular disease burden.

“From a cardiology perspective, I do think it’s important to realise that most people with cardiovascular disease don’t have FH – they have mildly elevated LDL–c level,” Professor Dart said.

“FH is not common, but coronary heart disease is.

“Look for people with an increased risk of coronary heart disease. Don’t become obsessed with FH,” Professor Dart said.

Latest news from doctorportal:

more_vert

more_vert