ALL facets of cardiac care, from prevention to rehabilitation, must be optimised to save more lives, say experts, after research finds invasive cardiac procedures are being used inconsistently.

Dr Ian Scott, director of internal medicine at Prince Alexandra Hospital in Brisbane, told MJA InSight that a lot of attention has justifiably been focused on invasive cardiac care, because when it is used appropriately, it is very effective in reducing mortality.

“[However], when considering all deaths due to coronary artery disease, long term pharmacotherapy and secondary prevention have proportionately greater effects on the natural history of coronary artery disease and in reducing overall mortality rates.”

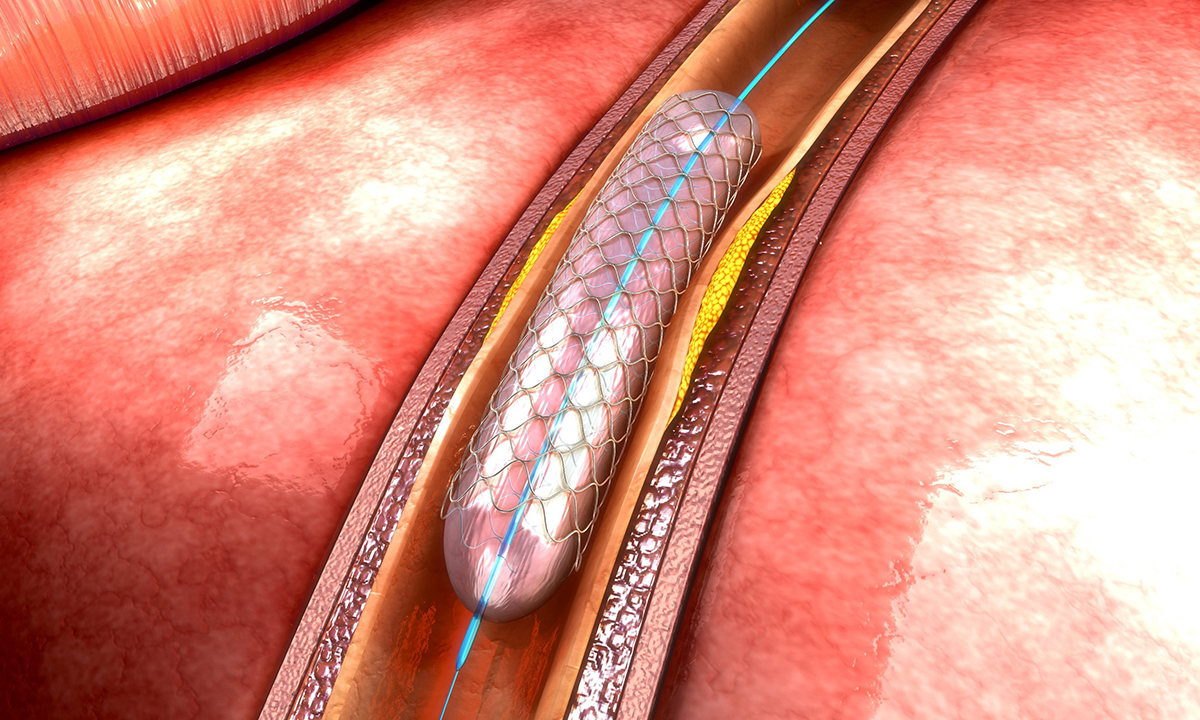

Dr Scott was commenting on research published in the MJA which analysed data from 61 former Medicare Locals to determine socio-economic, health workforce and service indicators associated with variation in angiography rates.

The authors found that acute coronary syndrome (ACS) incidence rates varied 3.7-fold between Medicare Locals, and angiography rates varied 5.3-fold. A higher probability of undergoing coronary angiography was associated with only a modest reduction in ACS mortality rates.

Socio-economic disadvantage and remoteness were associated with disease burden, ACS incidence and mortality, but not with angiography rate. The strongest association with local angiography rates was with admissions to private hospitals.

“Significant variation in providing coronary angiography, not related to clinical need, is evident across Australia.”

The authors said that a greater focus on clinical care standards and better distribution of health services will be required if these disparities are to be reduced.

Lead author of the study and professor of cardiology at Flinders University, Derek Chew, said that “the key thing we found is that when [coronary angiography] is used appropriately, we can see a mortality benefit, but if a large number of people are receiving it, then it’s not associated with an improvement in mortality”.

“The critical driver of the variation in care is reimbursement in the private versus the public system,” he told MJA InSight.

Professor Chew said that when it comes to addressing the inconsistency in invasive cardiac care, “there isn’t just a first step, there needs to be a contribution from all bodies and not just the funders, but also from the organisations involved in the safety and quality of health care, as well as from professional organisations”.

“Most of this practice is being driven by primary care, where patients are getting referred for angiography because [the GP] is concerned about them having a cardiac event. It’s a multifaceted approach that we need.”

Professor Chew also said that one of the biggest obstacles to effectively addressing inconsistencies in care will be establishing clinical indicators.

“We need to have agreed criteria and this will answer the question as to who should be getting therapy.”

Dr Scott authored an accompanying editorial, where he wrote that the inconsistency in the use of invasive care “cannot be allowed to persist into the next decade”.

He wrote that the problem in providing universal access to invasive care according to need lay within front line health care delivery.

“Cardiology service networks at the state level should collect data on ACS incidence and rates of invasive care in public and private facilities, identify locations where the mismatch is greatest, and seek to understand and mitigate the relevant factors.”

Dr Scott told MJA InSight said that it was important to recognise the variation in roles and responsibilities in managing ACS right across the health system.

“The responsibility for acute invasive care is concentrated in a relatively small group of health professionals working in a well organised and controlled environment, whereas responsibility for ongoing chronic care is diffusely spread across a variety of health care settings, which are less amenable to quality control mechanisms and system level improvement.”

He said that a collaborative approach that tied together treatment, rehabilitation and secondary prevention was needed.

“We need to optimise patient participation in cardiac rehabilitation programs following the acute event and their adherence over the long term to cardio-protective medications, and risk reduction in terms of smoking abstinence, low cholesterol diet, physical exercise, weight reduction, and control of diabetes and blood pressure.”

Dr Scott said that it was well known, for example, that up to 50% of patients stop taking their statins and other essential medications within a year after an acute event, and more than a third never participate in a cardiac rehabilitation program.

To help address this, “we need general practices to work closely with cardiac rehabilitation service providers in ensuring every patient with coronary artery disease has a chronic disease management plan which commences soon after the patient is discharged from hospital”.

He said that GPs and cardiologists also need to maintain a register of every patient they treat with coronary artery disease, which means patients are subject to regular reviews of risk factors and their adherence to medications.

Professor Chew said that, ultimately, “prevention is a lifelong commitment that lies in the community, and it extends from how we approach health care”.

“If we want an efficient health care system, this needs to come from the ground up and not from the specialists down,” he said.

Latest from doctorportal:

* Another baby in gas bungle at Sydney hospital

* Keyhole vs open prostate surgery?

more_vert

more_vert