MORE conservative patient selection means Australia is better placed than other countries to successfully implement catheter ablation as a treatment for a rising tide of atrial fibrillation, say local experts.

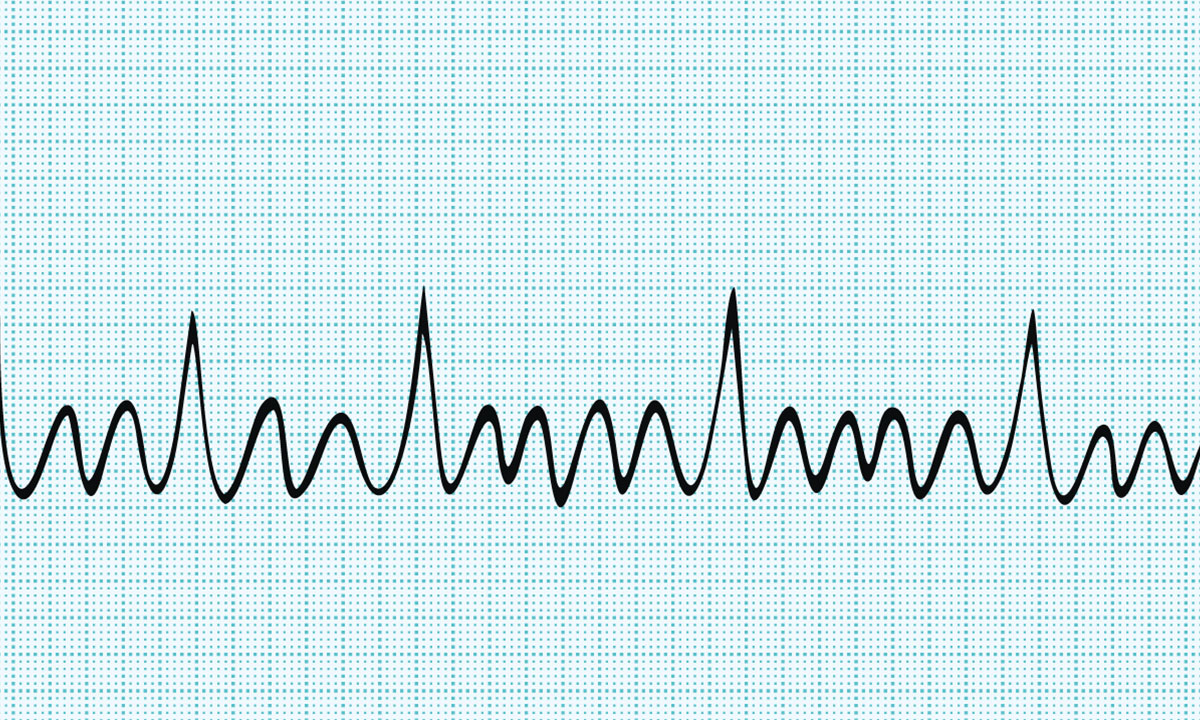

Associate Professor John Amerena, from Deakin University Medical School and director of Cardiac Services at Geelong Private Hospital, told MJA InSight that by 2050 there are expected to be 1.5 million Australians with atrial fibrillation (AF).

AF ablation rates in Australia increased between 23% and 40% per year over the 10 years from 2000–01 to 2009–10, depending on the data source, more than any other cardiovascular procedure, according to the authors of a 2013 study published in Europace.

A consensus statement from the National Heart Foundation published in the MJA in 2013 recommended that “the primary indication for catheter ablation of AF is the presence of symptomatic AF that is refractory or intolerant to at least one Class 1 or Class 3 antiarrhythmic medication”.

- Related: MJA InSight — Screen for AF

- Related: MJA — All that is irregular is not AF!

- Related: MJA InSight — Status quo for β-blockers in AF

“In selecting patients for catheter ablation of AF, consideration should be given to the patient’s age, duration of AF, left atrial size and the presence of significant structural heart disease,” the authors wrote.

Associate Professor Amerena said that patient selection was key to the success of AF ablation and that Australian specialists were “more conservative” than their US and European colleagues, who would “ablate anything even before trying drug therapies”.

Associate Professor Amerena was reacting to an article written by American doctor and journalist John Mandrola, who suggested that there was a possibility that “ablation of atrial fibrillation is no more effective than a placebo”.

“We’re much more selective and stringent [about who we ablate],” Associate Professor Amerena said. “If it’s proven that medication has failed, if the patient has the right anatomy, or is highly symptomatic – only then do we consider ablation.

“The older the patient is, the less likely ablation is to be successful. It’s the younger males who don’t want to spend the rest of their lives on medication who are more likely to want to try ablation and in whom it is most likely to be successful.

“Because we are very selective, it’s very uncommon for patients to need to go back for repeat procedures – that’s the exception rather than the rule,” he said

“Most Australian cardiologists have got the balance pretty right, I think.”

Nevertheless, Associate Professor Amerena said there was still room for improvement on the National Heart Foundation recommendations, suggesting more specific, “appropriate criteria” be applied to AF ablation, as well as other cardiovascular procedures, such as angiography and stenting.

“That has not happened here yet, but I think it will come, probably driven by the insurance companies,” he said.

Research into AF treatments tends to focus on ablation techniques than drug therapy, Associate Professor Amerena said.

“In terms of techniques, cryoablation is being compared with radiofrequency ablation, and we’re waiting on the results of trials of early ablation versus drug therapy.

“In terms of drugs, there has been nothing new on the horizon for a long time.”

Professor Prash Sanders, co-author of the National Heart Foundation consensus statement, and director of the Centre for Heart Rhythm Disorders at the University of Adelaide, told MJA InSight that the idea of ablation being no better than placebo was “absurd”.

“Any interventional procedure will have an element of a placebo effect – that cannot be denied,” he said. “[But] with AF ablation, there is a defined endpoint – the absence of AF – which is objective.

“There have also been numerous random controlled trials that have evaluated AF ablation against what is available (drug therapy) that have demonstrated superiority for suppression of symptoms.”

Last week was Atrial Fibrillation Awareness Week.

Latest news:

• Health policy in play as Coalition licks wounds

• Victoria on measles alert as infections mount

• No serious complications when antibiotics not prescribed – study

• Mass exodus of headspace board

more_vert

more_vert

So, the older more difficult patient, who might well have a further life to lead, gets tossed into the bin marked “He might have spoiled my good record”. So much for him.

Explain to me how this is not true.