WHILE outreach services are pushing into new territory in remote parts of Australia to eliminate the disparities in Indigenous eye health, experts say government funding is urgently needed to maintain services.

Professor Hugh Taylor, Harold Mitchell professor in the Indigenous Eye Health Unit (IEHU) at the University of Melbourne, told MJA InSight that there had been strong sector involvement and commitment from medical and public health organisations to closing the gap in vision care.

“But the problem is not a lack of cooperation between the different communities. The problem is that we really need a commitment from the federal government to make eye health a national priority.”

Professor Taylor was commenting on an MJA “Clinical Focus” article he co-authored on the progress of the ‘roadmap’ to close the gap for vision for Indigenous Australians. The roadmap was developed after extensive nationwide consultation, and launched in 2012. (1)

It included 42 recommendations that aimed to increase the accessibility and uptake of eye care services by Indigenous Australians, improve coordination between eye care providers, primary care and hospital services, improve awareness of eye health among patients and doctors, and to ensure culturally appropriate health services. (2)

The MJA authors wrote that a key part of the roadmap was the establishment of collaborative regional networks to coordinate and oversee activities. This group of key local stakeholders included Aboriginal health services, the local hospital district, primary care, optometry and ophthalmology practitioners, and public health authorities. To date, 12 regions have initiated this process, covering five jurisdictions and about 35% of Indigenous Australians.

In the 3 years since the launch of the roadmap, demonstrable gains had been made and there was growing momentum behind the roadmap initiatives, but there was still much that needed to be done, the authors wrote.

“In partnership with Indigenous communities and organisations, the public health and medical communities have a responsibility to engage with this effort and help close the gap for vision.”

The authors said that “with concerted multisectoral effort, political will and a commitment to establishing a sustainable eye care system, the gross disparities in eye health that exist between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians can be eliminated”.

Associate Professor Brad Murphy, chair of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners National Faculty of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health, told MJA InSight that a crucial factor not discussed in the article was the training and ongoing support that the IEHU provided to GPs working in regional communities.

Professor Murphy said the support available was like “having a ‘phone-a-friend’ system — we can take photos of a patient’s eyes and send them to ophthalmologists for assessment”.

He believed this could mean the difference between diagnosing a severe condition that would require flying a patient out for specialist treatment, and diagnosing a more minor problem.

However, Professor Murphy said that cost was the ultimate obstacle to closing the vision care equity gap, because initiatives were still significantly reliant on “philanthropy and good will”.

Professor David Atkinson, Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine spokesperson and head of the University of WA’s rural clinical school, agreed, saying that government rebates for retinal photography alone would be considerably helpful.

However, he told MJA InSight that there were certain regions in Australia where attempts to increase the provision of eye care services for Indigenous people were making inroads.

“Services are reasonably good in the Kimberley and while they could be improved, they are better than some other aspects of [Indigenous] health care because vision is a popular cause there”, Professor Atkinson said.

Ophthalmologist Dr Angus Turner directs Lions Outback Vision, a clinical outreach team set up by the Lions Eye Institute to provide specialist eye health care services to Indigenous communities in the Pilbara, Kimberley, Goldfields, Midwest and Great Southern regions of WA. (3)

He told MJA InSight that access to the equivalent diagnostic and imaging equipment, now commonplace in urban centres but not available elsewhere, “is a challenge when planning best management for eye conditions”.

“To overcome this, the Lions Eye Institute is embarking on a mobile eye health facility that will transport state-of-the-art equipment around the state”, Dr Turner said.

However, more funding would be needed to ensure communication channels between visiting and resident healthcare providers and patients could continue to operate.

Dr Turner said that Lions Outback Vision still had to mount a case to justify the continuation of 12-month pilot projects, each of which “takes a large amount of advocacy and resources”.

“It can often feel like we are returning to the drawing board as systems for funding constantly shift and the goal-posts change”, Dr Turner said.

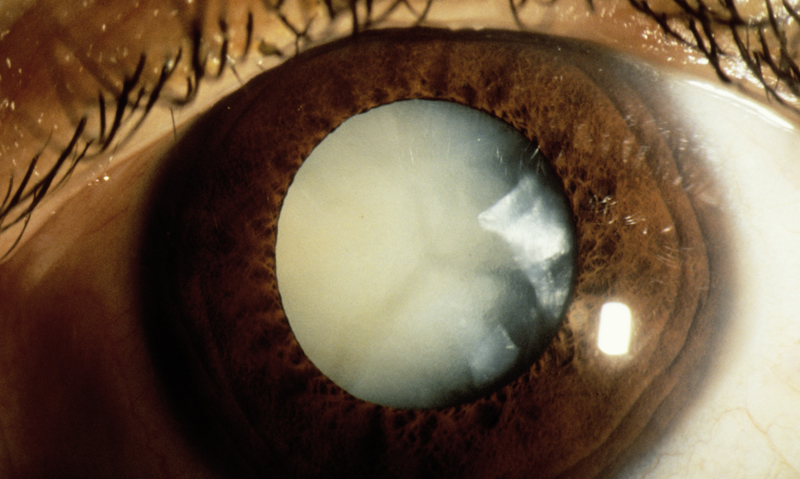

(Photo: Western Ophthalmic Hospital / Science Photo Library)

more_vert

more_vert