PANCREATIC cancer is throwing up many hurdles that require a new approach from cancer researchers, according to a leading medical oncologist and researcher.

Dr Lorraine Chantrill’s comments come as the MJA publishes an editorial today that warns the disease is likely to become one of Australia’s leading causes of cancer death as slow increases in incidence outpace improvements in outcomes. (1)

Dr Chantrill, from the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, told MJA InSight progress in treating pancreatic cancer was lagging behind other cancers partly due to the inaccessibility of the pancreatic tissue.

“It also relates to the rapidity of a patient’s decline in this disease, from diagnosis to death in advanced pancreas cancer is often only a few months. We don’t have very much time up our sleeves to do research on those people unfortunately”, said Dr Chantrill, who is also a medical oncology staff specialist at the Macarthur Cancer Therapy Centre in Sydney.

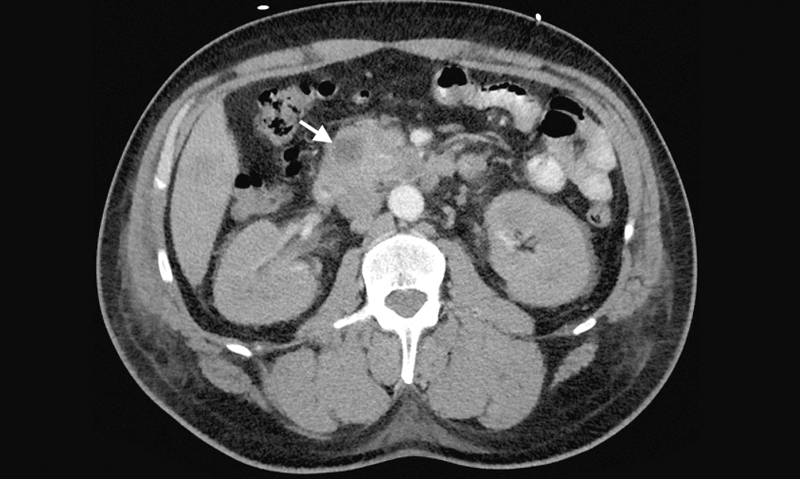

The MJA has also published a case report about a previously healthy 47-year-old African American man who presented to a Sydney hospital with suspected first-onset diabetic ketoacidosis and was later found to have pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The patient died 35 days after first presentation. (2)

The report authors advised a high degree of clinical suspicion of primary pancreatic disease in patients presenting with features of type 2 diabetes mellitus with first-onset diabetic ketoacidosis.

The editorial authors detailed the many challenges presented by the disease and noted that if current international trends were reflected in Australia, pancreatic cancer was likely to become one of the leading causes of cancer death within the next decade.

They wrote that between 1987 and 2007 in Australia there was only a 6% decline in pancreatic cancer mortality compared with a 34% drop in mortality from lung cancer, 47% from bowel cancer and 28% from cancers overall.

Last month Dr Chantrill announced an overhaul of the Individualised Molecular Pancreatic Cancer Therapy (IMPaCT) randomised controlled trial after being unable to sign up any of the 22 eligible patients. (3)

The research team, who hope to target treatment to three different groups of gene mutations found in about 15% of pancreatic cancer patients, found that patients were hesitant to postpone treatment until the biopsy results were known or to agree to randomisation.

To make the research program more accessible to patients, the researchers have now amended the trial to be single-arm and will provide patients with the best-available treatment while waiting for the gene sequencing results.

Dr Chantrill is hopeful that these amendments will improve the trial’s accessibility, with an aim of having 10 people in the study by the end of the year.

“We can’t give up just because it’s too hard, we have to try different ways of doing things,” she told MJA InSight.

Dr Rachel Neale, a coauthor of the MJA editorial and senior research fellow at the Queensland Institute of Medical Research, told MJA InSight a further challenge in tackling pancreatic cancer was its lack of early warning signs.

“The early warning signs are so non-specific that if GPs chose to send all people with those symptoms off for pancreatic-specific scans, it would blow the [health budget].”

Dr Neale said early signs such as abdominal and back pain were too non-specific to justify screening, and other symptoms, such as weight loss and jaundice resulting from the tumour pressing on the bile duct, signalled advanced disease. Evidence was also lacking on the benefits of early detection.

“Even though a very small proportion of people have a diagnosis at a stage where the tumour is able to be removed, … the survival of those people is not good”, she said, adding that there was a high risk of metastatic disease.

Dr Neale said a multipronged approach was needed to reduce the mortality from pancreatic cancer.

“We need to find better screening tests, we need to find better treatments, but we also need to just recognise that we could prevent a lot of these occurring in the first place”, she said.

“About 25% of pancreatic cancers occurring today are attributable to smoking. If we could completely wipe out all smoking, we would reduce the number of people dying from pancreatic cancer markedly.”

Type 2 diabetes and obesity were also associated with pancreatic cancer, and lifestyle modification could attenuate this risk.

Dr Chantrill agreed prevention was important, saying there was mounting evidence that patients with blood sugar-control issues — including those with a new diagnosis of diabetes and those with existing diabetes who had trouble with blood sugar control — should have an abdominal ultrasound to check for pancreatic abnormalities.

“I don’t think this has reached mainstream medical practice, but I think the evidence is building for the association of diabetes and pancreas cancer”, she said, adding that the MJA case report underlined this association.

1. MJA 2015; 202: 401-402

2. MJA 2015; 202: 444-445

3. Garvan Institute: Media release 20 April 2015

(Photo: MJA)

more_vert

more_vert