ONLY half of living kidney donors in Australia have had at least one follow-up by the transplant unit or referring hospital in the first 3 years after the operation, prompting experts to call for more consistent reporting.

Data from the living kidney donor register created in 2004, which is part of the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA), show that while all transplanting units contribute information about living donors at baseline, rates of submitting follow-up data for individual units range from 0%–100%.

Associate Professor Stephen McDonald, ANZDATA executive officer, said until about a decade ago the usual practice was not to follow up donors at all.

The ANZLKDR shows that about 55% of donors in the 2008–2011 cohort were followed up at least once compared with about 40% in the original cohort.

Professor Paolo Ferrari, director of nephrology at Fremantle Hospital in WA, said while early complication rates in live donors were quite well documented, long-term complications were poorly documented.

“Long-term follow-up of donors should be more consistent, in order to provide early detection and management of conditions that may be a risk for chronic kidney disease [CKD] or, if CKD occurs, that it’s treated appropriately”, he said.

More than 4100 living kidney donations were performed in Australia between April 1991 and December 2012, he said.

A US study published in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, has found a lack of comprehensive, long-term follow-up of living kidney donors. (1)

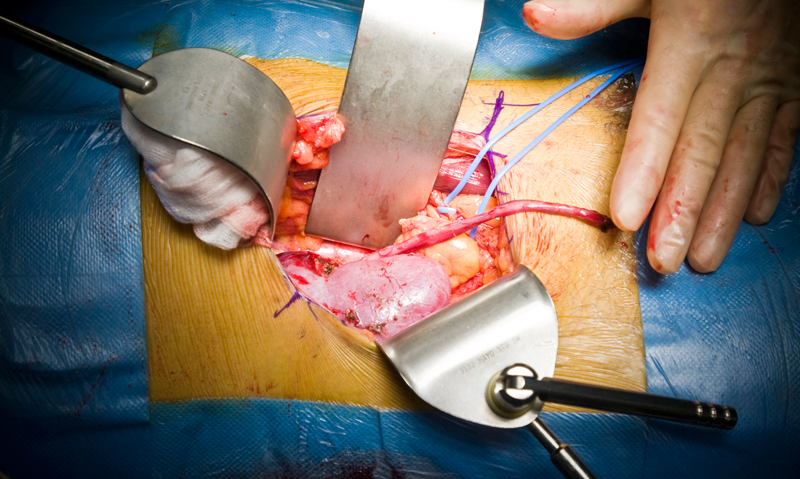

The study of 69 117 living kidney donors in the US, capturing data from the National Inpatient Sample from 1998 to 2010, showed the procedure-related complication rate was about 8% and had decreased over time. Those most likely to suffer complications were men and donors with hypertension.

However, the presence of some comorbidities in donors had increased significantly, including diagnoses of depression and hypothyroidism, and hypertension, which more than tripled over the period. The number of donors with obesity also increased substantially.

The complication rates and length of hospital stay for living donors were comparable to patients undergoing appendicectomies and cholecystectomies but were less than those with nephrectomies for carcinoma.

“Monitoring the health of living donors remains critically important”, the study authors wrote.

Professor Jeremy Chapman, director of renal medicine at Westmead Hospital in Sydney, said the US study findings were compatible with the Australian experience, where there was a trend to broadening the strict criteria for comorbidities in living donors.

“What it highlights for us in Australia is the need to support the ANZDATA of living donors and ensure we provide good long-term follow-up data on our donors”, he said.

Professor Ferrari said ANZDATA analysis of 2400 living kidney donations had shown about 18% had at least one relative contraindication and 10% had one absolute contraindication.

Dr Tim Mathew, the national medical director of Kidney Health Australia (KHA), said there was overwhelming evidence from large US databases, which tracked living donors for 20 years or more, that if they were submitted to rigorous work-up excluding important comorbidities pre-donation, health outcomes were not adversely affected.

“There [has been] a tendency in the past 5‒10 years, and that’s true in Australia as well, to be pressured into taking donors who are not what we would have in the past called perfect, that is, they have a bit of high blood pressure and occasionally even a bit of glucose intolerance”, he said.

“There are risks associated if the agreed criteria are not followed. There are boundaries beyond which we should not go.”

Dr Mathew said more live donors were needed, with a 33% reduction in the number of donors in the past 4 years and a waiting list of 6 months to 4 years for deceased kidney donations.

The federal government was funding a review, at KHA’s request, to better understand the reasons for the decline. “No one understands the significant and continuing downturn”, Dr Mathew said.

It was imperative to collect long-term data on live donor outcomes, he said. “The longer we go without establishing Australian-based outcome data, the longer it is going to take to get a good answer.”

An editorial accompanying the US study said by improving understanding of short- and long-term health outcomes among representative, diverse samples of living donors, the processes of consent, selection and care, which were vital priorities, could be improved. (2)

1. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; Online 26 September

2. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; Online 26 September

more_vert

more_vert