TRAUMATIC brain injury is particularly challenging when it comes to public health interventions.

Although traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a largely preventable form of acquired central nervous system injury, it is not always reported and managed through formal health care services. Even in its milder forms, TBI can produce cognitive and behavioural changes that can have profound impacts on the lives of sufferers and their families.

Outcomes for people who suffer a TBI can include impairments in educational attainment, work capacity, social interactions and personal relationships.

Alarm bells about the consequences of TBI should be ringing even louder following a recent article in The Lancet Neurology on the incidence of such injury in a defined population in New Zealand.

This study sought to capture all TBI cases in the city of Hamilton and the surrounding rural Waikato district in 2010–2011, using a subject identification strategy that extended from injury cases not just presenting to hospital but also to a variety of community settings.

Using reasonably traditional criteria for grading a TBI (eg, Glasgow coma scale, post-traumatic amnesia), the study demonstrated an incidence of 790 cases per 100 000 person-years. Previous studies on TBI incidence have been largely based on retrospective data analysis and case classification, and have varied dramatically in incidence rates, with estimates of between 200 and 600 cases per 100 000 person-years.

The NZ study also demonstrated that 95% of the cases were “mild” in terms of classification, indicating a substantial underreporting of TBI cases through the hospital setting. About 70% of TBI cases were children and young adults, and mostly males.

This public health scenario of greater than expected incidence rates is intimidating enough, but given the association of TBI with other neurodegenerative conditions, there is reason for further concern. This includes heightened risk of dementia in the elderly, as well as a recent review from the US indicating that multiple mild forms of brain injury (eg, in American football and ice hockey players, as well as combat veterans) may lead to specific Alzheimer disease-like neurodegenerative brain changes (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) causing dementia, personality changes and depression in young adults.

Together, the research raises the spectre that milder forms of brain injury in the population may be producing health and societal outcomes of substantial impact.

Amateur players of Australia’s three most popular football codes (Australian football, rugby league and rugby union) frequently sustain concussion and subconcussive injury. However, most Australian recreational and school sports teams lack medical personnel trained in the detection and assessment of concussions in the paediatric population.

As a result, some young athletes may suffer undiagnosed concussion, which increases the risk of repeated head trauma that can result in lasting neurocognitive and developmental deficits leading to psychiatric conditions.

In a recent British study more than 70% of incarcerated male juvenile offenders reported at least one TBI incident in their lifetime, raising the concern that such injury may cause long-lasting brain changes that contribute to subsequent criminal behaviour.

The NZ study clearly highlights that the societal impacts of TBI are likely to be underappreciated, particularly in the paediatric and young adult population, and emphasises that a public health approach that alerts the health, sporting and general community to the risks of single and repeated brain injury, even at the mild end of the spectrum, is increasingly necessary.

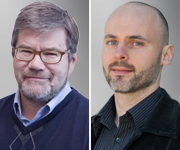

Professor James Vickers is co-director of the Wicking Dementia Research and Education Centre at the University of Tasmania. Dr Frederic Gilbert is a research fellow specialising in neuromedicine at the University of Tasmania.

Posted 29 January 2013

more_vert

more_vert