A WORLDWIDE push is underway to radically change the way medical devices are regulated, including improved communication between global regulators.

A UK investigation last week has increased concerns about metal-on-metal hip implants. The joint BMJ/BBC investigation found hundreds of thousands of people worldwide with metal-on-metal hip implants may have been exposed to dangerously high levels of cobalt and chromium ions causing local reactions that destroy muscle and bone, leaving some patients with long-term disability and possibly carcinogenic effects. (1)

The UK investigation adds weight to mounting evidence that an urgent device regulation revamp is needed internationally, including in Australia as outlined in a series of articles in the latest MJA.

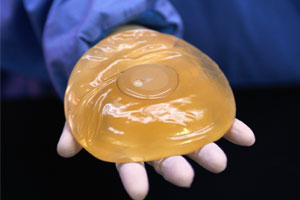

The UK investigation found problems with metal-on-metal hip implants had been known and documented for decades. Problems with the hip implant could affect more people than those affected by a breast implant that has been recalled by French breast implant maker Poly Implant Prothése (PIP).

The hip implant revelations are described as the latest in a series showing Europe’s medical device regulation system was not “fit for purpose”. The investigation showed that new types of hip implants did not have to undergo clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy before being used.

An article discussing the ongoing problems with metal-on-metal hip implants in the BMJ said that although no premarket system could ensure all devices are safe, “they can certainly make it more likely”. (2)

Also on the topic of device failure, research in this week’s MJA examined instances of guide-wire fragment embolisation in four commonly used peripherally inserted central catheters in children, and identified problems in the current regulatory approach taken by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). (3)

The research showed the problems occurred in 1.4 of 100 insertions of one particular device, but a TGA review only required improvements to labels and user instructions while finding no inherent flaw with that device, the authors wrote.

The authors found there was currently no standardised, published methodology for dealing with this type of safety issue.

A spokeswoman for the TGA said specific articles about peripherally inserted central catheters were published by the TGA in late 2008. (4)

Another study in the latest MJA examined data publicly available on the TGA’s website and identified several periods of time where medical device incident data were unavailable between January 2000 and December 2011, with no clear explanation for this. (5)

The authors said that this made it difficult “to make informed decisions about the safety of any given device” and called for greater transparency.

The TGA spokeswoman said information currently on the TGA website was only intended as a snapshot of data collected. She said since 2001 the TGA had routinely published on its website statistics on reports submitted to its medical device incident reporting investigation scheme.

The spokeswoman said following the release of the report TGA reforms: A blueprint for the TGA’s future, the TGA was working on ways to improve information provided to consumers and the broader healthcare community.

An accompanying editorial in the MJA said because the Australian regulatory system only mandates testing of “high-risk” devices, most medical devices on the market had not had any assessment or premarketing testing undertaken by the manufacturing companies, as found in the BMJ investigation. (6)

Postmarketing assessment was also a problem due to underreporting.

The editorial noted that most product recalls in Australia were company initiated, and these were not listed on the TGA website and did not carry a requirement to notify regulatory bodies in other countries.

The editorial acknowledged a heavy responsibility if the regulator, rather than the company, makes a recall decision. In 2008, the TGA was ordered to pay millions of dollars in damages after withdrawing Pan Pharmaceutical’s licence and recalling more than 200 of its products. (7)

“To make [a recall], the TGA needs to be confident that the need to recall is well supported by facts. An error in the decision to withdraw could lead to significant compensation to the company and cost to the Australian public”, the MJA editorial said.

“At the moment there appears to be an excellent opportunity to make significant enhancements — not only nationally, but internationally — to enhance the quality of regulation. All stakeholders, but most particularly patients, will stand to benefit if this occurs”, the editorial said.

The BMJ article was also critical of postmarket surveillance, finding that regulators in the US and Europe failed to spot problems despite concerns being raised.

“Creating an independent system for post-marketing analysis for implantable medical devices that is robust and increasing international coordination around device alerts and withdrawals should go some way to sorting out the current mess”, the article said.

– Amanda Bryan

1. BMJ 2012; 344:e1410

2. BMJ 2012; 344:e1349

3. MJA 2012; 196: 250–255

4. TGA: Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC lines)

5. MJA 2012; 196: 256–260

6. MJA 2012; 196: 222-223

7. Pan class action’s $67.5m settlement. The Australian 2011; 26 Mar

Posted 5 March 2012

more_vert

more_vert