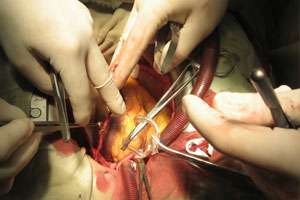

RESEARCHERS have called for perioperative practice and guidelines to include the use of statins in patients undergoing high-risk cardiac surgery following a systematic review showing a significant reduction in adverse events.

The meta-analysis of 15 randomised controlled trials involving nearly 2300 patients, published in the Archives of Surgery, showed reductions in postoperative complications in statin naive patients who were commenced on statins around the time of their surgery. (1)

Most of the 15 trials identified involved cardiac surgery, in which the risk of atrial fibrillation was reduced by 44%. When cardiac and non-cardiac surgery studies were combined, myocardial infarction was reduced by 47% and duration of hospital stay by 32% in patients taking perioperative statins. No effect on mortality was demonstrated.

The review authors said the precise mechanisms by which statins reduced perioperative adverse events were uncertain, but noted that statin treatment tempers systemic and vascular inflammation.

“These results suggest that perioperative practice and guidelines should be modified to incorporate greater use of statins in patients undergoing surgery”, they wrote.

“The present analysis suggests that it may be appropriate for future guidelines to be broadened to endorse statin treatment in specific statin-naive populations, such as those undergoing high-risk procedures (eg, intra-abdominal, intrathoracic or cardiac surgery) or those at high risk for cardiac events (eg, unstable coronary artery disease).”

An accompanying critique described the findings as “significant … with real implications for patient care and cost containment”. (2)

However, it noted that there were caveats, including that the findings were dominated by cardiac surgery patients, and there was no mention of postoperative complications or adverse events such as increased blood loss.

The critique said that based on the data presented “statins should be given to statin-naive patients undergoing cardiac surgery and probably major vascular procedures as well”. It was less clear how the findings should be applied to noncardiac procedures.

Professor Garry Jennings, director of Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, said although the meta-analysis extended previous analyses suggesting patients do better after cardiac surgery if started on statins preoperatively, a randomised trial would be needed to test whether the same benefits occurred in all surgical procedures.

“Most of the patients contributing to the meta-analysis had cardiac surgery but the finding seems to extend to vascular surgery procedures and hints at benefits after non-vascular surgery”, Professor Jennings said.

“The latter groups need further evaluation but as most patients undergoing vascular surgery are likely to have some degree of coronary artery disease, it is not unreasonable to suggest that they might benefit from interventions that are found to be helpful in people undergoing coronary surgery.

“This empirical observation seems enough to suggest that all patients having coronary or vascular surgery who are not receiving a statin should be commenced prior to surgery whenever possible. The downside is likely to be minimal, the benefits significant, and most have indications for long-term therapy anyway”, he said.

Associate Professor Stuart Thomas, of the department of cardiology at Westmead Hospital, Sydney, said most of the patients in the study would have had an indication for statins. He said this emphasised the importance of prescribing statins for patients who met current guidelines indicating statin therapy.

“A more useful question would be whether statins reduce the risk of significant perioperative complications in patients with no other indication for statin therapy”, Professor Thomas said.

“These results are interesting and important but it would be a mistake to assume they could be generalised to a broader group of surgical patients.”

– Amanda Bryan

1. Arch Surg 2012; 147: 181-189

2. Arch Surg 2012; 147: 189

Posted 27 February 2012

more_vert

more_vert