DOCTORS prescribing gentamicin need to be more vigilant in monitoring for evidence of potentially devastating vestibulotoxicity as soon as possible after starting a patient on the drug, two leading Australian specialists have warned.

In an editorial in this week’s MJA, Professor John Turnidge, of the University of Adelaide, and Dr John Waterston, of the neuroscience department at Monash University, said early recognition of vestibulotoxicity and stopping gentamicin therapy may prevent progression and potentially lead to some recovery. (1)

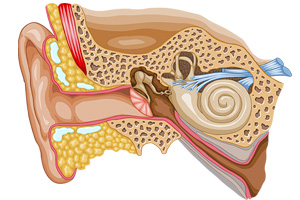

They suggested that, if possible, doctors should avoid or limit the use of gentamicin in patients with a history of pre-existing inner ear or balance disorders.

However, they wrote that aminoglycosides, including gentamicin, were still the mainstay of therapy for serious gram-negative infections, because widespread resistance in both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria had not been observed in these drugs. This compared with newer antimicrobial class drugs in which the potential for resistance and multiresistance was recognised.

Their warning follows the publication of research that reviewed patients with severe bilateral vestibular loss associated with gentamicin treatment in hospital. (2)

The authors of the research, which identified 103 patients with imbalance, oscillopsia or both due to gentamicin, found those prescribing gentamicin failed to recognise vestibulotoxic symptoms. Even when patients reported imbalance that developed after hospital admission, gentamicin was rarely considered as the possible cause.

“Unless clinicians know how to test for bilateral vestibular loss, gentamicin treatment will not be stopped and vestibulotoxicity will most likely be aggravated”, the study authors wrote.

They said bilateral vestibular loss could now be objectively confirmed at the bedside using tests such as dynamic visual acuity.

“Our report of 103 cases seen over 23 years suggests that vestibulotoxicity is rare. However, our criteria excluded patients in whom we were unable to obtain dosing and clinical details, those with pre-existing renal failure and those with partial bilateral and unilateral vestibulotoxicity”, the authors wrote.

They said gentamicin vestibulotoxicity could occur with any dose, in any regimen, at any serum level and was often not recognised.

Professor Turnidge and Dr Waterston wrote that the cardinal symptoms — motion-induced dizziness, oscillopsia and gait ataxia — might not become apparent until patients start to mobilise. “Prescribers need to be more vigilant in monitoring for evidence of vestibulotoxicity in conscious patients and, as soon as practical after starting gentamicin, using methods such as the dynamic visual acuity test”, they wrote.

Even in severely ill bed-bound patients symptoms could be minimal. They said that it was not often appreciated that gentamicin vestibulotoxicity does not cause spontaneous vertigo.

However, they said aminoglycosides should still play a role as initial therapy.

“Therapeutic guidelines: antibiotic presents the latest thinking: retain the therapeutic benefit of low rates of resistance and known efficacy, while attempting to minimise the risk of toxicity”, Professor Turnidge and Dr Waterston wrote. (3)

“Essentially this means prescribing aminoglycosides as empirical therapy for up to 48 hours, pending culture results, and then changing to appropriate but safer therapy when the results of tests are known.”

– Kath Ryan

1. MJA 2012; 196: 665-666

2. MJA 2012; 196: 701-704

3. Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic version 14, 2010

Posted 18 June 2012

more_vert

more_vert