THE value of collecting real-world cancer data has been highlighted by the findings of an Australian study of women diagnosed with non-metastatic breast cancer.

The researchers sought to determine how many of the 6644 women on the NSW Central Cancer Register went on to develop the metastatic form of breast cancer (BC). Their findings, published in the latest issue of the MJA, provide important new information about prognosis. (1)

They found that for those with regional cancer (that is, with spread to regional lymph nodes or adjacent tissues), the risk of developing metastatic breast cancer (MBC) within 5 years was 18% (1 in 6), while 5.3% (1 in 20) of those with localised cancer (confined to breast tissue) went on to develop MBC.

Even internationally, very few population-based studies had examined MBC incidence in patients with non-metastatic BC at initial diagnosis, according to the researchers. “Clinicians can use these estimates to inform women with BC about the average risks of developing MBC”, they wrote.

“Although clinical trials can provide data to estimate the incidence of MBC for selected BC populations it is unclear to what extent trial estimates, which are drawn from patients receiving care from participating institutions who meet trial eligibility criteria, apply to the general population with cancer.”

The researchers found that women aged less than 50 years and those living in areas of lower socioeconomic status were most at risk of MBC. Also, the chance of being diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer was highest in the second year after initial breast cancer diagnosis.

“This information may provide some reassurance for women who completed their primary breast cancer treatment more than 2 years ago and remain recurrence free”, the researchers wrote.

According to cancer experts, this research is a great illustration of the clinical importance of cancer registries. However, they said the information held by these registries was currently too limited.

“The main trouble is they have limited staging information so when it comes to determining whether cancer survival has improved, it’s hard to separate the effects of screening programs”, said Dr Roger Allison, director of cancer care services at Royal Brisbane Hospital.

Improvements in screening and treatment were not mutually exclusive and both contributed to lessening the disease burden, but it was important to know when improvements were the result of treatment, Dr Allison said.

“Staging information is important for all cancer, not just breast cancer, but it needs a comprehensive nationwide approach”, he said.

Professor Max Schwartz, head of the medical oncology unit at The Alfred, Melbourne, said national databases that captured outcomes would not just help clinicians but could also guide funding decisions.

The key to their success would lie in not setting out to collect too much data. Instead, it was important to try to identify and collect only the most critical information — but the catch lay in getting nationwide agreement, Professor Schwartz said.

Cancer Australia had been championing work in this area, its chief executive, Professor Helen Zorbas, told MJA InSight.

It has developed a cancer clinical dataset, which identifies the essential data to be collected across all cancers, as well as a data dictionary.

Professor Zorbas said the aim of these was to enable uniform and consistent data collection across different cancer treatment centres.

She said two Cancer Australia pilot projects were also underway to look at how to best source that essential data prospectively, for example through laboratory results or medical records.

“Through this paper, we now have clearer understanding of time frames and common sites of metastases in relation to disease stage. Once we have national clinical data, we can also map what treatment these patients received, which can better inform our cancer control activities”, she said.

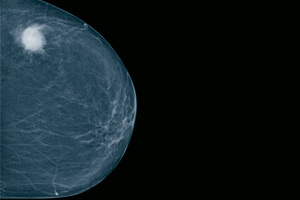

In other research published in the MJA, false-positive mammogram results were found to deter women from attending further screening appointments, undermining the effectiveness of breast cancer screening programs. (2)

– Amanda Bryan

1. MJA 2012; 196: 688-692

2. MJA 2012; 196: 693-695

Posted 18 June 2012

more_vert

more_vert