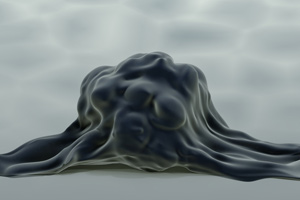

THE presence of circulating tumour cells is an independent predictor of relapse and death in chemotherapy-naive patients with non-metastatic breast cancer, according to new research.

Australian oncologists say the results of the research are interesting, and ongoing research will show whether circulating tumour cells (CTCs) will be a useful biomarker for prognosis in the future.

The research, published in The Lancet Oncology, assessed 203 chemonaive patients with stage 1–3 breast cancer undergoing surgery for their primary tumour, with a median follow-up of 35 months. (1)

Patients with at least one CTC detected in a peripheral blood sample taken at the time of surgery showed decreased progression-free survival at 2 years, and a greater proportion relapsed compared with patients who had no CTCs.

Tumour size or other primary tumour characteristics did not reliably predict CTCs.

“HRs [hazard ratios] increased with rising numbers of circulating tumour cells. Two or more circulating tumour cells predicted significantly worse overall survival”, the researchers wrote.

“Remarkably, even with a relatively short follow-up there were significantly worse outcomes in patients with one or more circulating tumour cells.

“Furthermore, the identification of one or more circulating tumour cells showed greater HRs for both relapse and death than almost all of the variables currently used to assess prognosis in patients with operable breast cancer; higher numbers of circulating tumour cells carried HRs as prognostically powerful as lymph-node metastasis.”

The researchers said the results supported the idea that information on CTCs should be included in staging algorithms for patients with non-metastatic breast cancer, “especially as it provides important biological information on the metastatic process”.

A comment in the same issue of The Lancet Oncology said the research should be the catalyst for more detailed investigations as the importance of CTCs as biomarkers in early stage malignancy could not be ignored. (2)

Associate Professor Jacquie Chirgwin, a medical oncologist in Melbourne and chair of the ANZ Breast Cancer Trials Group board, told MJA InSight that although the study results were interesting, they were not conclusive.

“It is important to have larger numbers, more events and a thorough multivariate analysis before concluding that this test provides additional prognostic information beyond what is currently available”, Professor Chirgwin said.

She said there was no evidence that knowing whether patients had CTCs would improve outcomes.

“If it does, as the authors suggest, provide additional prognostic information, there is also no evidence that it has any predictive role in determining if additional treatment will have efficacy.”

However, Professor Chirgwin said it was not unreasonable to record CTC results in staging algorithms but it should “remain in the experimental field and not for the care of patients”.

Associate Professor Fran Boyle, director of the Patricia Ritchie Centre for Cancer Care and Research at the University of Sydney, said blood was being collected for CTCs in all current adjuvant breast cancer trials internationally, “so that in future we may be able to validate their usefulness as a biomarker of prognosis”.

“After that, a trial will need to be designed where treatment is altered on the basis of finding CTCs, eg, giving more chemotherapy … Meanwhile, testing requires shipment of samples overseas and significant cost to patients, which has not been validated as a decision-making tool and thus would be discouraged”, Professor Boyle said.

Professor John Boyages, director of the Macquarie University Cancer Institute, said new research programs at the institute would examine the impact of CTCs on prognosis and whether they should be used as a guide to alter therapy.

“A key question is whether the circulating tumour cells are biologically active or whether they could be merely dispersed during surgery without the genetic changes necessary for them to grow in other parts of the body such as the liver or the bone”, Professor Boyages said.

Identifying which circulating tumour cells are important and which are simply another marker in the diagnosis of breast cancer would be important research strategies in the future, he said.

– Kath Ryan

1. Lancet Oncology 2012; Online 6 June

2. Lancet Oncology 2012; Online 6 June

Posted 12 June 2012

Don’t miss next week’s issue of the MJA for the latest Australian research on survival after breast cancer.

more_vert

more_vert