US researchers recommend replacing cytology with a form of human papilloma virus testing as the primary screening test for cervical cancer, but Australian experts are wary, saying more local evidence is needed.

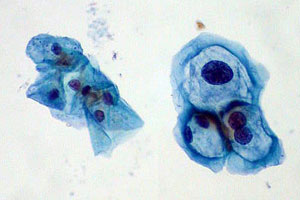

The research, published in The Lancet Oncology, involved 42 000 women who had cervical specimens tested with liquid-based cytology and HPV DNA testing. Various HPV tests were used, including the second-generation Roche cobas test which enables detection of HPV16 and 18. (1)

In agreement with previous research, HPV testing was found to be more sensitive but less specific than cytology. Among women referred for colposcopy, the sensitivity of the cobas HPV test was 92%, compared with 53% for the liquid-based cytology, for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN3) or worse.

The specificity of the two tests for identifying women with CIN3 was 57% for the cobas HPV test, compared with 73% for liquid cytology.

However, when researchers identified which HPV-positive women had HPV genotypes 16 and 18, the test was more effective at detecting CIN3 or worse. Compared with cytology, the sensitivity was slightly higher (60% vs 53%), as was the positive predictive value (15.5% vs 14.1%).

“HPV testing with separate HPV16 and HPV18 detection could provide an alternative, more sensitive, and efficient strategy for cervical cancer screening than do methods based solely on cytology”, the researchers wrote.

“… use of HPV testing as the primary screening test to rule out disease, and use of a specific test, like liquid-based cytology, to decide which women need immediate colposcopy, seems to be a rational approach”, they said

HPV genotypes 16 and 18 are associated with about 70% of all invasive cervical carcinomas and are targeted by the cervical cancer vaccine.

Adjunct Professor Annabelle Farnsworth, director of cytology at Douglass Hanly Moir Pathology, said the research was one of the first major studies looking at the cobas HPV test.

“What the research is trying to say is that if you come up with HPV high-risk positive, then the women most at risk of developing significant disease are the ones that are 16 or 18 positive. So they’re suggesting using genotyping as a triage to try and make the HPV test have a higher positive predictive value.”

However, Professor Farnsworth said more Australian research was needed, especially because Australian cytology was more sensitive than overseas cytology for detecting high-grade lesions.

“A lot of research says, ‘HPV testing is so much better, throw away cytology and do HPV testing’. But it’s not that simple, and it’s not that simple in Australia.”

“I think the thing that’s interesting about this paper is that it illustrates how complex the whole issue is.”

Currently, in Australia, HPV DNA testing only attracts a Medicare rebate if it is done as a ‘test of cure’ for women who have been treated for high-grade intraepithelial lesions, as recommended by the NHMRC Guidelines for the management of asymptomatic women with screen-detected abnormalities. (2)

Professor Farnsworth said there was a whole raft of new tests becoming available which could prove useful as the population of women vaccinated against HPV increases.

Associate Professor Karen Canfell, an epidemiologist with the Cancer Council NSW who has published widely on cervical cancer screening, said the genotyping could identify women at elevated risk of serious disease, irrespective of their vaccination status.

“Some women may have been vaccinated but may have already been exposed to HPV”, she said.

However, Professor Canfell said that any change to Australia’s cervical screening program had to be supported by a comprehensive evidence-based package including a systematic review of primary HPV screening trials and studies, cost-effectiveness and epidemiologic modelling and perhaps local clinical evaluation.

Professor Canfell said a randomised trial of primary HPV screening in Australia is in early planning stages.

– Sophie McNamara

1. Lancet Oncol 2011; August 23 (online)

Posted 29 August 2011

more_vert

more_vert

This is exciting news and may be the quantum leap that scattered Pacific Island countries could implement. With small populations and limited technical support or treatment options, HPV DNA screening combined with an HPV vaccine program is achievable and certainly could adrress the high CaCx rates that developing countries now demonstrate.